The Story of One Woman’s Fight for a Better Society

Holocaust

to Resistance: My Journey – A Review Essay

Suzanne Berliner Weiss

Roseway Publishers, 2019

Interview with Suzanne Weiss Wednesday 1 March 2023

I first met

Suzanne Weiss through organising the Socialist

Labour Network’s Holocaust Memorial Day meeting on 27 January 2023. Suzanne

had, prior to this, sent me a copy of her book, Holocaust to Resistance: My Journey. Below is a review article I

have written.

Tony Greenstein

From Holocaust

to Resistance - Suzanne Weiss

Suzanne Weiss has written one of the most moving books I’ve read.

Suzanne is a living, walking symbol of the slogan Never Again for Anyone. The Nazi Holocaust– which devoured millions

of lives, Jews, Gypsies, the Disabled, to say nothing of trade unionists,

communists and socialists – did not spring out of nowhere.

The Holocaust wasn’t, as western propaganda pretends, an act

of madness, ‘a pseudo-messianic ideology.[1]

which saw the Jews as being the incarnation of the Devil.[2] Nazism

was a product of imperialism, the belief that the West had a divine right to

plunder, pillage, rape and murder those it colonised.

As Edwin Black wrote:

The Nazis' extermination

programme was carried out in the name of eugenics …. In France, Belgium,

Sweden, England and elsewhere in Europe, cliques of

eugenicists did their best to introduce eugenic principles into national life;

they could always point to recent precedents established in the United States….

From the turn of the

century, German eugenicists formed academic and personal relationships with the

American eugenics establishment, in particular with Charles Davenport, the

pioneering founder of the Eugenics Record Office on Long Island, New York,

which was backed by the Harriman railway fortune. A number of other charitable

American bodies generously funded German race biology with hundreds of

thousands of dollars, even after the depression had taken hold.

Black described how Hitler proudly

told his comrades how closely he followed American eugenic legislation:

Now that we know the laws of

heredity’ he told a fellow Nazi, ‘it is possible to a large extent to prevent

unhealthy and severely handicapped beings from coming into the world. I have

studied with interest the laws of several American states concerning prevention

of reproduction by people whose progeny would, in all probability, be of no

value or be injurious to the racial stock

Alt Samia Central United Church, 2017

The Nazis were,

above all, imperialists. Nazi economic and foreign policy was based on lebensraum, the conquest of ‘empty

spaces’ in Eastern Europe. On 5 November 1937, Hitler addressed the German High

Command emphasising that he intended to wage wars of plunder in Eastern Europe.

The record of the conference was known as the ‘Hossbach

Protocol’. The Incorporated Territories, which Germany later conquered in

Poland, were to be cleared of Jews, Poles and Gypsies.

SLN

Holocaust Memorial Day Meeting, Suzanne

Weiss 27 01 23

Suzanne Weiss

was born of Jewish refugee parents in France in 1941. In 1943 the Jewish

resistance dispersed thousands of Jewish children into the countryside,

including Suzanne. She was looked after for the next two years by a French farm

family in Auvergne province. Then, in 1945, her dying father, accompanied by a

friend who purported to be her mother, came to the village and took her back to

the Jewish community. For the next four years Suzanne was shunted from one

orphanage to another before being adopted by a Jewish couple in America.

Troubled Teen 1954

Suzanne had

a difficult childhood growing up in the United States with two domineering

adoptive parents, Frances and Louis Weiss. Louis insisted that the only role of

a woman was to procreate. Although they were on the anti-McCarthyite left and

supported the struggle of America’s Black population for liberation, Suzanne’s

adoptive parents were aghast when Suzanne invited home a young Black man. They

wanted him to come in the back door lest the neighbours see! An injunction that

Suzanne ignored.

Yet when Suzanne

asked Viola, a Black woman who cleaned the apartment, and cared for her,

whether it was true that Africans cooked and ate white people, Suzanne was

reproached for asking a Black person such a question. ‘Where did you get such an idea’ her mother asked her as if she had

invented it. In fact, the young Suzanne was questioning the prevailing racist

bias of American society.

Growing Up in New York

Reading

this difficult personal story, which intertwines with her growing political

awareness, I was shocked that her new parents could be so insensitive to a young

orphan who had lost a mother in Auschwitz and a father to the fight against the

Nazis. Frances even told her that she hadn’t been their first choice to adopt. ‘I wanted Nicole’ referring to a friend

in the orphanage. They were bull-headed and determined that Suzanne would grow

up in their own image. The first part of the book is about Suzanne’s

determination to map out her own life.

Pensive and conflicted, 1958

After one

heated argument in which Suzanne ran to

her room and slammed the door, Louis took that door off its hinges! Many

similar incidents followed. Frances was ‘emotionally

remote’ Suzanne recalls. Her new parents

‘didn’t understand that they had adopted

a child with a tumultuous background whose personality had already been

formed.’ They provided material necessities but not for her emotional

needs.

A subtext

running throughout the book is Suzanne’s search for information on who her

birth parents were and what had happened to them. Her adoptive parents had

various documents and photographs yet did not share them.

Suzanne

tells a miraculous story of how a school friend introduced her to Nora, who turned

out, amazingly, to be Suzanne’s birth mother’s sister. Nora’s spouse, Jake,

turned out to be a notorious Jewish collaborator with the Nazis in their Polish

home town of Piotrkow Trybunalski. From Nora Suzanne learnt that her mother had

been an activist in the Bund, a Jewish anti-Zionist party that commanded

majority support amongst Polish Jews.

When

Suzanne revealed her discovery of Nora to her adoptive parents, they gracefully

accepted it. But after a party in celebration of this addition to the family,

her adoptive father launched into a tirade dictating Suzanne’s future: ‘the female role is to find a mate and to

multiply.’ Angered, Suzanne fled from her home and sought refuge with a girlfriend.

Suzanne’s adoptive parents reacted by having Suzanne arrested and incarcerated

in a detention facility – as it happened, a Catholic girl’s residence for

delinquents. As she was remanded into custody, Suzanne observed that Louis ‘had learned

nothing from the McCarthy Witchhunt’. When

the residence staff asked whether she was really Jewish, Suzanne replied

coldly, ‘Hitler made me Jewish’. Today

one might equally reply that Zionism has also made us Jewish.

After her

release, Suzanne’s problems did not ease. When she was given a recording by Gertrude Stein, the

American lesbian poet and novelist, Suzanne’s paranoid adoptive father hired a

private detective to follow her.

Suzanne and

her adoptive mother moved to Los Angeles in an attempt to cut off the

friendship with her New York friends. Suzanne paid for her own post office box

in order that she could communicate with her friends safe from the prying eyes

of her adoptive parents.

At a French orphanage

The American Socialist Workers Party

The second

part of the book takes up Suzanne’s work in the American Socialist Workers

Party (SWP), and her role in establishing its print shop. This was the time of

the Cuban Revolution, the continuing struggle for Black rights, Women’s rights,

and the campaign against the Vietnam War.

In 1960, the

Holocaust was a hot topic because of the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem. When a

friend asked Suzanne if she was a Zionist she responded

No, I’m Jewish. I didn’t see how Israel as a Jewish

country could be the answer to the hatred of the Jews. Besides wouldn’t it be a

convenient place to get rid of us all at once.

Suzanne concluded

that ‘Never again’ was not only a

Jewish slogan about Nazism but also applied to the whole of humanity.

In August

1959 as Suzanne left for a new life in San Francisco her adoptive mother

lamented that they had had only had nine years together. Upon reflection

Suzanne noted that

I rebelled against the insincerity,

dishonesty and hypocrisy of these ‘progressives’. They who railed against

McCarthyism, used his tactics.

In June

1960 Suzanne married and left with her husband for a honeymoon in revolutionary

Cuba.

On their

return, Suzanne joined in building the Fair

Play for Cuba Committee, – dangerous

work since exiled-Cubans were armed and threatening. Suzanne recalls how at one

Fair Play for Cuba meeting a group of

Cubans attacked the meeting. Fortunately, the stewards were prepared for them

and fought back, ejecting them out into the street.. An exile fired a gun (at

an undercover cop!). However, there followed harassment and surveillance by the

FBI against the supporters of the Cuban revolution.

This whole

period was one of struggle for Black liberation, the assassination of Kennedy

and then Malcolm X, and the growth of the anti-Vietnam war movement.

When

Suzanne succeeded in obtaining a small sum by way of holocaust reparations she

was determined to give it away to those struggling to end apartheid in South

Africa and the SWP. Her adoptive parents insisted that she should keep it

herself, and rather than praising her selflessness, cut her out of their will

(although in her old age her adoptive mother relented). Suzanne observed that

it was ‘a hard blow to a fragile

relationship.’

With Suzanne's birth mother, Fajka Berliner

Another application

for reparations brought not payment but a cache of new documents about

Suzanne’s parents and what had happened to them. She learnt that her birth mother

had arranged for her rescue by the Jewish resistance.

From civil

rights campaigns to Vietnam anti-war campaigns, Suzanne was immersed in

solidarity action. At a time when many Communists and socialists were calling

merely for negotiations to end the Vietnam War, Suzanne was explicit in the demand

for American troops out. She refused to accept the legitimacy of the American

presence.

Throughout

her narrative Suzanne skilfully interweaves the personal with the political.

She describes the sexism of her male comrades. When Suzanne narrowly escaped

being raped in New York, her comrades joked about how women really enjoyed

being raped.

The

pervading sexism in both the SWP and American society as a whole, is a constant theme. It was

a sexism that not only put women down but also had the effect of inhibiting

their participation in the movement. Although the SWP was transformed by the

women’s liberation movement, Suzanne’s own immersion in the print shop, cut her off

from the living movement. It is a problem that afflicts all Marxist groups and

reproduces itself as sectarian isolation.

When the

SWP decided that its members should become factory workers, Suzanne took on a

number of manual jobs in factories and the oil industry. The jobs were dirty

and at times dangerous. She sought to prove that women had equal rights to

those of men.

Her

description of the American working class, which in private industry was barely

unionised, shows how the effects of both racism and sexism weakened the class.

Her friends and companions were Black women. In one workplace in the South the

clerks objected to her eating her lunch with Black workers. ‘You’re a Yankee and we’re segregationists’ they

proudly boasted, along with references to Hitler as a ‘great man’. They

preferred a segregated workplace even though these divisions played into the

hands of the bosses. This backwardness of workers is rarely addressed by the

left, other than as an example of ‘false consciousness’.

In 1979

Suzanne got a job with an oil company and encountered the hatred of the white workers

for Black workers: ‘my idealised concept

of union solidarity was shattered by reality.’ In 1981 the air traffic

controllers union PATCO struck for increased pay and better working conditions.

President Reagan fired them, over 11,000 strikers. ‘The total lack of a union response sealed Reagan’s victory,’ Suzanne commented.

Yet the party leaders

continued to stress, like a hammer knocking on our brain: ‘The workers are

moving to centre stage of the class struggle.’ How’s that? Get off cloud nine and face reality I thought’.

And here we

see how the far-left, addicted to its template of working- class revolution

never understands why there is no revolution. Instead, the different groups

retreat into the theory of inevitability and ignore difficult theoretical

questions such as whether or not the western working class is indeed the

gravedigger of capitalism or whether it has been compromised by racism and

imperialism.

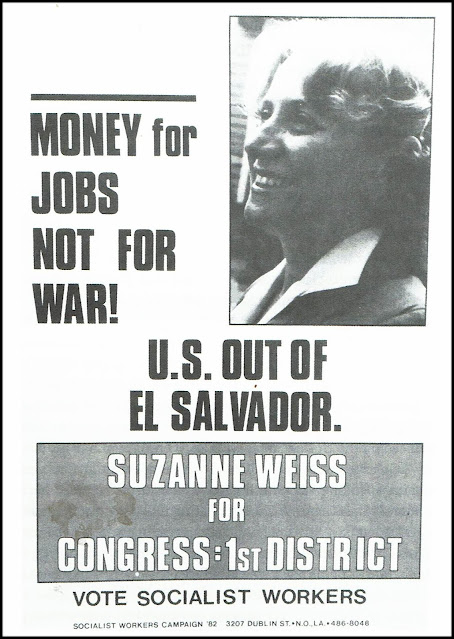

In 1982, Suzanne

stood as a socialist candidate for Congress, winning positive nominal support

of fellow workers – but no co-workers actually came to her rally. ‘The party remained an alien milieu for my

workmates. Our socialist message was not in harmony with their lives and

concerns.’

It was this

divorce from reality that led Suzanne to lose her enthusiasm for the party.

Perhaps the

most gratifying episode in the book is Suzanne’s initiative in finding a new

partner. Having settled on John Riddell she asked him to dinner! Like all fairy

tales it ended up in a happy marriage with someone Suzanne could trust and

cherish.

Suzanne

played a significant role in the SWP for 33 years, during which time she was

entrusted with organizing the care of James P. Cannon, a founder and prominent

leader of the SWP.

In the

years after Cannon’s death, Suzanne records, the SWP increased its sectarian

and undemocratic path excluding all criticism. What had been a promising socialist

group became a sect under the control of a leadership which brooked no dissent.

It was a

leadership which refused to allow reality into its political vision. Suzanne

had been working alongside the American proletariat, and had won their respect,

but it was clear that they would not get involved in the SWP. The party’s experiment

of sending their cadre into factories was not working.

Although

she does not mention it, this experiment was not unique. Very similar things

happened with the PATCO Reagan British SWP and Trotskyist groups like the

International Marxist Group (IMG) who also sent their middle-class cadre into

factories in the hope that they would provide the spark that would light the

fires of working-class revolution.

What

neither the SWP, the IMG or other tiny groups of the Marxist left understood

was that the working class in the West was not automatically a revolutionary

class. They had been corrupted by the crumbs from the imperialist table, hence

why nationalism and racism were so endemic amongst workers in the West. They

had supped with the devil but without a long spoon!

The final

part of the book recounts Suzanne’s return to France with her partner, John. She

had sworn never to return to the land where she had experienced the terror of

Nazism but, after a time John, persuaded her. This is perhaps the most

optimistic part of the book where Suzanne learnt of the fight of the French

resistance and how, in the area where she had been hidden, Auvergne, 5,000 Jewish

children had been hidden. This was as many as the total saved during the war by

the illegal immigration (Aliya Beit) to Palestine, the only form of rescue

acceptable to Zionism.

In France, Suzanne

met up with Michel Berman, who had first looked after her when her father

retrieved her from Auvergne. She learned of the activities of the UJRE (Union

of Jews for Resistance and Mutual Aid) which had protected her from the Nazi

killers.

Suzanne visited

her father’s grave and found it marked with a cross. ‘No justice even in

death’. She also found the Nazi record of her own mother’s journey to Auschwitz

and learnt of the complicity of the French Vichy police in the arrest of Jews.

Although the Vichy regime shielded Jews born in France, it offered up the

refugee Jews to the Nazis.

This is the

answer to Zionism’s belief that Jews can only be safe living in their own state

and replicating the racism that they had experienced. It was not Zionism that

saved Suzanne or the thousands of Jewish children in France, Belgium and other

countries but the solidarity of ordinary workers and peasants and their

resistance to Nazism. At the same time the Zionists staffed the Judenrat

(Jewish Councils) which, almost without fail, collaborated with the Nazis over

and above their duty.

As Suzanne

cut her last links with the SWP, she judged that its politics ‘had become more and more contrived and

brought no understanding, no clarification, no lessons learned.’ She moved

with John to Toronto to begin a new life. Obtaining a degree at university, she

became a care counsellor for the elderly:

Suzanne

wondered ‘whether elderly Holocaust survivors differed from survivors of other

traumas, tragedies or genocides such as Palestinian families’. She pondered how

Palestinian survivors of the Naqba were subjected to daily terror, the

destruction of their families and the loss of their homes, possessions and

homeland.

By the year

2001 the entire older generation in Suzanne’s family had died:. ‘I look back with regret on the older

generation with all its passionate courage and hurtful short-sightedness.’

There is a

chapter on Nora’s husband Jake’s collaboration with the Nazis, which is an

issue I have wrestled with in my book Zionism

During the Holocaust. Suzanne quotes Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi who

distinguished between collaboration under coercion from voluntary

collaboration. I had independently reached the same conclusions. It is

something that Lenni Brenner in his 51

Documents – Nazi-Zionist Collaboration fails to make. As Suzanne observed: ‘Responsibility for the personal tragedy of

his (Jake’s) wartime role lies with

the Nazis, who made thuggery and betrayal the road to survival.’

The point

about Zionist collaboration with the Nazis was that it was voluntary. No one

forced the Zionists to offer a trade agreement Ha'avara to the Nazis. No one

forced the German Zionist Federation to write a letter to Hitler on 21 June

1933 pledging co-operation. No one forced Rudolf Kasztner to testify at Nuremberg

on behalf of the Jewish Agency in support of Hermann Krumey, the butcher of the

children of Lidice and Hungarian, Austrian and Polish Jewry. This was the crime

of Zionism. Its collaboration was voluntary.

In sum, Cuba,

Venezuela, Bolivia Solidarity, and indigenous sovereignty were all causes

Suzanne embraced in recent decades. In the process, she says, ‘I broke from long held prejudices against

left-wing activists who were not Marxists.’ Climate change pointed to new

directions. Yet Suzanne regretted the absence of a socialist party which could

have integrated all these struggles if only it had not been consumed by

sectarian dogmas.

On

receiving a request in 2005 to sign a letter protesting at the visit of Israeli

war criminal Ariel Sharon, Suzanne signed it with the words ‘holocaust

survivor’. She had come out. As she observed:

Hitler’s Holocaust is unique

in history. Nothing is similar to it. Still, many Israeli techniques – the

expulsions, the ghetto isolation, the pervasive checkpoints – have a disquieting

resemblance to Nazi methods.

Perhaps

here we disagree. Every genocide is unique but was the Holocaust any different

from the extermination of Native Americans by Andrew Jackson or the Armenian

genocide, at which German army officers were present who would later carry out

the extermination of Jews? Was not the extermination of Africans at Namibia’s

Shark island concentration camp the precursor of the Holocaust? Its commandant

Dr Eugene Fischer later training Nazi doctors such as Joseph Mengele.

To those who

say comparisons between Israel and Nazi Germany are anti-Semitic my reply is

that we should compare more not less. In so far as Israel uses the Nazi

holocaust as its justification we are under a duty to point out the

similarities.

I was

pleased to discover that Suzanne was involved in campaigns against Israeli

companies Ahava and Sodastream since I too was heavily involved in these

campaigns in Britain. As Suzanne says ‘my

allegiance to the Palestinian freedom struggle contributes to my affirmation of

my Jewishness.’

In the

chapters on her visits to Auvergne, Suzanne remarks on how, on at least five occasions,

German soldiers had deliberately ignored the presence of Jewish children. The

community of Chambon was overflowing with children, a quarter of whom were

Jewish, as well as German soldiers. This is an important corrective to the idea

that all Germans were anti-Semites. Hitler came to power not because of

anti-Semitism but despite it.

The German

army was, to be sure, guilty of many atrocities not least its collaboration

with the Einsastzgruppen. But it also

protested in Poland at the attacks by the Nazi SS on Jews.

In the

penultimate chapter Suzanne describes her interviews in Paris with Le Figaro. ‘Whilst thanking the people who courageously hid the Jews and other

refugees ‘in plain sight’, I also drew the parallel with the fate of refugees

today.’ It is this which Zionism refuses to do since it too pursues the

chimera of racial purity.

Suzanne

summed up her defence of Palestinian freedom:

My whole being has been

intertwined in this irrepressible striving for social justice. My mother and

father were Jewish socialists, looking for solutions to hatred and injustice.

They were opposed to the Zionist settlement of Palestine. I stand with them and

oppose the colonialism that has displaced and oppressed the indigenous

Palestinians.

It is not

surprising that Suzanne has left behind her, at the age of 82, the sectarianism

of far-left groups but continues to embrace the struggle of the Palestinians

while also persisting in her commitment to the goal of socialism. If the first

part of her life saw the end of Apartheid in South Africa it is to be hoped

that we will also soon see the end of Apartheid in Palestine.

This is a

book that I cannot recommend highly enough.

a moving and evaluative/ critical review, Tony, and a very remarkable book/ testimony by Suzanne Weiss. Thanks for posting. Dave Hill

ReplyDeleteAnother excellent piece written about one Phenomenal Woman. Thank You.

ReplyDelete