In September 1868, Southern white Democrats hunted down around 200 African-Americans in an effort to suppress voter turnout

It is the 150th

anniversary of the most notorious massacre in Afro-American history. It took place in Opelousas in the St Landry parish of Louisiana. Following the American Civil War (1861-65)

there followed the era of Reconstruction when

the 11 Confederate States were integrated with the North. It was an era in which the Black slaves were

freed and in which the Southern White Supremacists attempted to cling on to

their power. As Blacks were being enfranchised the old Southern White establishment reacted. It was an era of the

KKK and of many bloody

massacres and lynchings.

For those who see the Democrats as the left-wing or more

progressive party it should be noted that in the 19th century it was

the Republicans who were the integrationists and the Democrats who were the

bastion of White supremacy and segregation. As late as

the 1968 Presidential election Democratic segregationism was represented in

American politics by George

Wallace, the 3rd party candidate and former Governor of Alabama

who won 13.5% of the vote in the Presidential election and 32 electoral college

votes. He bears a number of similarities to Donald Trump.

The article below commemorates the 150th

anniversary of the Opelousas

massacre. It makes sober reading. Matthew Christensen writes

that:

The St. Landry Massacre is representative of the pervasive violence and intimidation in the South during the 1868 presidential canvass and represented the deadliest incident of racial violence during the Reconstruction Era. Southern conservatives used large scale collective violence in 1868 as a method to gain political control and restore the antebellum racial hierarchy. From 1865-1868, these Southerners struggled against the federal government, carpetbaggers, and Southern black populations to gain this control, but had largely failed in their attempts. After the First Reconstruction Act of March, 1867 forced Southern governments to accept universal male suffrage, Southern conservatives utilized violence and intimidation to achieve their goals, which escalated as the 1868 presidential election neared. Violence was nearly omnipresent in Louisiana during the presidential canvass and was the primary reason behind the Democratic victory in the state.

|

| A cartoon from a U.S. newspaper from 1880 reads: ’Terrorism in the South. Citizens beaten and shot at.” |

“E.B. Beware! K.K.K.”

So read the note found on the

schoolhouse door by its intended recipient: Emerson Bentley, a white school

teacher. He found the message in early September 1868, illustrated with a

coffin, a skull and bones, and a dagger dripping with blood. The

straightforward message represented a menacing threat to Bentley, who was

teaching African-American children in Louisiana at the time. Little could the

Ohio-born Republican have predicted just how soon that violence would come

about.

Bentley, an 18-year-old who also

worked as one of the editors of the Republican paper The St. Landry

Progress, was one of the few white Republicans in the Louisiana parish of

St. Landry. He and others came to the region to assist recently emancipated

African-Americans find jobs, access education and become politically active.

With Louisiana passing a new state constitution in April 1868 that included

male enfranchisement and access to state schools regardless of color, Bentley

had reason to feel optimistic about the state’s future.

But southern, white Democrats were

nowhere near willing to concede the power they’d held for decades before the

Civil War. And in St. Landry, one of the largest and most populous parishes in

the state, thousands of white men were eager to take up arms to defend their

political power.

The summer of 1868 was a

tumultuous one. With the help of tens of thousands of black citizens who

finally had the right to vote, Republicans handily won local and state

elections that spring. Henry Clay Warmoth, a Republican, won the race for state

governor, but the votes African-Americans cast for those elections cost them.

Over the summer, armed white men harassed black families, shot at them outside

of Opelousas (the largest city in St. Landry Parish), and killed men, women and

children with impunity. Editors of Democratic newspapers repeatedly warned of

dire consequences if the Republican party continued winning victories at the

polls.

Those editorials spurred Democrats

to action and instigated violence everywhere, wrote Warmoth in his book War, Politics, and Reconstruction: Stormy Days in Louisiana.

“Secret Democratic organizations were formed, and all armed. We had ‘The

Knights of the White Camellia,’ ‘The Ku-Klux Klan,’ and an Italian organization

called ‘The Innocents,’ who nightly paraded the streets of New Orleans and the

roads in the country parishes, producing terror among the Republicans.”

The vigilante groups were so

widespread that they often included nearly every white man in the region. One

Democratic newspaper editor estimated that more than 3,000 men belonged to the Knights of the

White Camellia of St. Landry Parish—an area that included only 13,776 white

people in total, including women and children.

With the approach of the

presidential elections in November, the tension only increased. On September

13, the Republicans held a meeting in the town of Washington, not far from

Opelousas, and found streets lined with armed Seymour Knights. A misfired rifle

nearly caused a riot to break out, but in the end, everyone departed

peacefully—though the Democrats threatened Bentley if he failed to publish an

“honest” account of the event in the St. Landry Progress. Sure enough, they

used Bentley’s account, in which he wrote the men had been intimidating the

Republicans, to instigate a wave of violence on September 28, 1868.

Displeased with the way Bentley

had portrayed the Democrats, Democrats John Williams, James R. Dickson (who

later became a local judge), and constable Sebastian May visited Bentley’s

schoolhouse to make good on the anonymous threats of the earlier September

note. They forced him to sign a retraction of the article, and then Dickson

savagely beat Bentley, sending the children who were sitting for lessons

scattering in terror. Rumors spread, and soon many Republicans were convinced

Bentley had been killed, though he managed to escape with his life. As a small

number of African-Americans prepared to rescue Bentley, word spread around the

parish that a black rebellion was imminent. Thousands of white men began arming

themselves and raiding houses around the area.

“St. Landrians reacted to armed

Negroes and rumors of an uprising in the same manner that Southerners had

reacted for generations,” wrote historian Carolyn deLatte in 1976. “If

anything, the vengeance visited upon the Negro population was greater, as

blacks were no longer protected by any consideration of their monetary value.”

On the first night, only one small

group of armed African-Americans assembled to deal with the report they’d heard

about Bentley. They were met by an armed group of white men, mounted on horses,

outside Opelousas. Of those men, 29 were taken to the local prison, and 27 of them were

summarily executed. The bloodshed continued for two weeks, with

African-American families killed in their homes, shot in public, and chased

down by vigilante groups. C.E. Durand, the other editor of the St. Landry

Progress, was murdered in the early days of the massacre and his body displayed

outside the Opelousas drug store. By the end of the two weeks, estimates of the

number killed were around 250 people, the vast majority of them

African-American.

When the Bureau of Freedmen (a

governmental organization created to provide emancipated African-Americans with

legal, health and educational assistance and help them settle abandoned lands)

sent Lieutenant Jesse Lee to investigate, he called it “a

quiet reign of terror so far as the freed people were concerned.” Influential

Republican Beverly Wilson, an African-American blacksmith in

Opelousas, believed black citizens were “in a worse condition now than in

slavery.” Another observer was led outside the town of Opelousas and shown the

half-buried bodies of more than a dozen African-Americans.

But Democratic papers—the only

remaining sources of news in the region, as all Republican presses had been

burned—downplayed the horrific violence. “The people generally are well

satisfied with the result of the St. Landry riot, only they regret that the

Carpet-Baggers escaped,” wrote Daniel Dennet, editor of the Democratic Franklin

Planter’s Banner. “The editor escaped; and a hundred dead negroes, and perhaps

a hundred more wounded and crippled, a dead white Radical, a dead Democrat, and

three or four wounded Democrats are the upshot of the business.”

The groups managed to achieve

their ultimate purpose, as was borne out by the results of the November

presidential elections. Even though Republican nominee Ulysses Grant won, not a

single Republican vote was counted in St. Landry Parish. Those who oversaw the election felt “fully convinced that no man

on that day could have voted any other than the democratic ticket and not been

killed inside of 24 hours thereafter.”

“St. Landry Parish illustrates the

local shift of power after 1868, where an instance of conservative boss rule

occurred and the parish Republican Party was unable to fully recover for the

remainder of Reconstruction,” writes historian Matthew Christensen. There would be no Republican

organization in the parish for the next four years, and no Republican paper

until 1876.

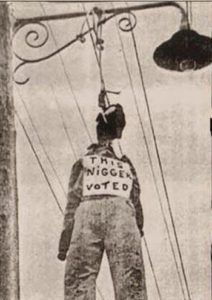

The Opelousas massacre also set

the stage for future acts of violence and intimidation. “Lynching became

routinized in Louisiana, a systematic way by which whites sought to assert

white supremacy in response to African-American resistance,” said historian

Michael Pfeifer, the author of The Roots of Rough Justice: Origins of American Lynching,

by email. “This would be an important precedent for the subsequent wave of

lynchings that occurred in Louisiana from the 1890s through the early decades

of the twentieth century, in which lynch mobs killed more than 400 persons,

most of them African American.”

Yet for all that it was the

deadliest instance of racial violence during the Reconstruction period, the

Opleousas massacre is little remembered today. Only slightly better known is

the 1873 Colfax

massacre in which an estimated 60 to 150 people were killed—a massacre

largely following the pattern set by Opelousas.

“The United States has done

comparatively little until quite recently to memorialize its history of

significant racial violence,” Pfeifer said. “Reconstruction remains contested

in local memory and efforts to remember the achievements of Reconstruction are

cancelled out by the seeming failure of the period to achieve lasting change.”

Lorraine Boissoneault is a contributing writer

to SmithsonianMag.com covering history and archaeology. She has

previously written for The Atlantic, Salon, Nautilus and others. She

is also the author of The

Last Voyageurs: Retracing La Salle’s Journey Across America. Website: http://www.lboissoneault.com/