How a Black Spy Infiltrated the Confederate White House, the Freedom Riders and 6 Heroines of the Struggle

It is Black History

Month and it is opportune to cover some of the heroes and heroines of America’s

civil rights struggle. It is noticeable how, in the United States, there is a

Holocaust museum in Washington but no equivalent institution to remember the

victims of slavery or to commemorate the struggle to end desegregation and the

fight against Jim Crow.

Very little if any

mention is made of the role of Black people in the American civil war, which is

depicted as a struggle between the good Whites of the North and the bad Whites

of the South. People like Mary Bowser (Richards) who worked in the home of

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy in Richmond Virginia.

|

| Elizabeth Van Lew |

Bowser had been freed

by Elizabeth Van Lew who used her inheritance to free Mary and other slaves.

Van Lew co-ordinated what was a veritable Black spy ring at the heart of the

Confederacy including Bowser. Another member of this spy ring was John Scobell.

The Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions Morgan v. Virginia (1946) and Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional.[3] The Southern states had ignored the rulings and the federal government did nothing to enforce them. The first Freedom Ride left Washington, D.C. on May 4, 1961, and was scheduled to arrive in New Orleans on May 17.

|

| Gloria Richardson, Dr. Rosa L. Gragg and Diane Nash |

Below are two

articles on the Freedom Riders and Diane Nash in particular. I have also copied

below a tribute to 6 Black heroines of the civil rights struggle. Coretta Scott King should be well known to

people but the other five are less well known.

Also there is an article on the late Congressman

John Lewis, who was arrested no less than 40 times. Lewis symbolised the

political co‑option of the Black struggle into the American power struggles.

Lewis, who campaigned against desegregation supported the Jim Crow State of

Israel. Nothing better demonstrates this than the fact that Jo Biden won the

Democratic nomination because of the vote of Black people in South Carolina and

elsewhere in the South on Super Tuesday.

This is the same Jo

Biden who started off his political life as a segregationist and who supported

the mass incarceration of Black people under Bill Clinton. There is a lesson

here for Black Lives Matter which is also showing signs of sinking into the

swamp of Black identity politics.

Tony Greenstein

Confederate President

Jefferson

Davis occupied an anxious home in Richmond, Virginia, during

the Civil War. A steady leak of information dripped from the highest ranks of

the Confederacy to the Union. Davis was wary of a mole in his house, but had no

idea how to stop the flow of information. Little did he know, a Union spy found

her way into deepest parts of the Confederate White House as part of an

abolitionist woman’s spy ring.

These women,

Elizabeth “Crazy Bet” Van Lew and Mary Bowser, a freed slave who posed as a

Davis’s servant, worked together to bring down the political fixtures of the

South from the inside out.

Spies were common on

both sides of the Civil

War. Van Lew organized a spy ring in the heart of the Confederacy and

Bowser, with her photographic memory and incredible acting skills, was able to

relay critical intelligence to Van Lew, which would then make its way to the

Union.

Spying on the most

elite members of the Confederacy required the deception of more than just the

enemy. In order to keep from exposing themselves, the women needed to fool

society around them. They opted to be labeled as senseless and stupid

instead of revealing themselves as the canny operators that they

were.

|

| Elizabeth Van Lew. (Credit: Virginia Museum of History & Culture/Alamy) |

Van Lew was born in

1818 into an affluent family in Richmond. After receiving her education as a

teenager in Philadelphia, she began to see the injustice of slavery throughout

the country. And as she got older, her stance against slavery only got

stronger, despite the fact that her family owned slaves.

Following her father’s

death in 1843, Van Lew and her widowed mother freed the slaves that the family

owned, and Van Lew used the money from her father’s death—$10,000 (about

$200,000 in today’s currency)—to buy and free the relatives of the

slaves that her family had owned.

“No pen, no book, no time can do justice to slavery’s

wrongs, its horrors,” Van Lew wrote in her diary, as reported by author Elizabeth R. Varon in the biography Southern Lady,

Yankee Spy: The True Story of Elizabeth Van Lew, A Union Agent in the Heart of

the Confederacy.

Among the many freed

slaves was young Mary Bowser, born Mary Jane Richards. Believed to have been

born between 1839 and 1841, Richards remained a servant for the Van Lew family

after attaining her freedom. Bowser was given special treatment from the time

she was baptized as an infant at the family’s church, and was sent by Van Lew

to the North, possibly Philadelphia, to receive a formal education. At the end

of Richards’ education, Van Lew dispatched her as a missionary to the West

African nation of Liberia in 1855.

Richards stayed in Liberia, which was founded by freed American slaves, until 1860, but was unhappy living there. When she finally came back to America, she was promptly arrested, likely because of a law that prohibited black Virginians who had lived in a free state or gotten an education from returning. She spent 10 days in jail before Van Lew paid her bail.

Richards used aliases

from the moment that she was apprehended to the time that she was released,

going by both Mary Jane Henley at her arrest and Mary Jones at her release—an

early precursor to her ability to take on the role or title that best

benefitted her scenario. The records that follow her life bear witness to the

many names she used. She married fellow Van Lew servant Wilson Bowser on April

16, 1861, and was then known as Mary Elizabeth Bowser. The Civil War erupted

just four days before the marriage.

Shortly afterward,

Van Lew began volunteering as a nurse at the tobacco warehouse in Richmond—the

capital of the Confederacy—that housed Union prisoners and would later become

known as Libby Prison. In July of 1861, she and her mother started to bring

food, clothes, books, medicine and other materials to the prisoners.

Unbeknownst to the

guards, Van Lew was unofficially helping the Union with her deliveries, hiding

messages and plans for escape in her deliveries. She even housed escaped Union soldiers, helping them as they tried

to make their way back to the North.

Van Lew’s assistance to enemies of the Confederacy was met with disdain in Richmond, where residents were proud of the pro-slavery stance that their government upheld, shunning—and sometimes threatening—those that were sympathetic to the Union cause. But under the guise of a false persona in which she mumbled nonsense and was easily distracted, “Crazy Bet” was left alone by her fellow Southerners.

Word of Van Lew’s

efforts to help the Union reached military

leaders in the North, namely General Benjamin Butler, who sent a

representative to recruit her as a Union spy. Under the instruction of Butler,

Van Lew started to grow her network of spies, having them deliver dispatches in

a colorless ink that could only be deciphered when milk was applied to the

page.

Van Lew’s most

valuable asset in her spy operation was Mary Bowser, who was able to spy for

the Union in an entirely different way: from the vantage point of a domestic

servant. After cleaning and cooking at several functions for the family of

Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Bowser was hired as a full-time servant

in the Confederate White House.

There, she swept and

dusted in the nooks and crannies of Davis home, reading the plans and documents

that were laid out or hidden in desks, and reporting her findings to Van Lew.

Equipped with a photographic memory, she was a troublesome spy to have behind

enemy lines.

There’s not much

information as to what Bowser was able to report back as a spy, as all of her

dispatches to Van Lew were destroyed out of fear that they would lead to severe

repercussions. However, Van Lew’s diary entries imply that Bowser’s reports

were critical in helping the Union navigate their way towards victory during

the war.

“When I open my eyes in the morning, I say to the

servant, ‘What news, Mary?’ and my caterer never fails!” Van Lew wrote.

“Most generally our reliable news is

gathered from negroes, and they certainly show wisdom, discretion and prudence,

which is wonderful.”

As the war came to a

close, in 1865, Van Lew was thanked personally by Union General Ulysses S.

Grant. “You have sent me the most

valuable information received from Richmond during the war,” he reportedly told her.

Grant even gave Van Lew money for her services to the Union. Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough to cover the money she had already spent operating a spy ring of more than a dozen people; she had largely exhausted her inherited wealth during the Civil War. Afterward, she was left poor and abandoned by her community after it was revealed that she was a Union spy.

On Van Lew’s

deathbed, in 1900, the story of Mary Bowser came to light in press accounts. In

the Richmond and Manchester Evening Leader, it was reported that Van Lew described a “maid, of more than usual intelligence” who was educated out of

state, sent to Liberia and planted as a servant to Davis during the war. A

decade later in a Harper’s Monthly interview, Van Lew’s niece, Annie

Randolph Hall, identified the woman as Bowser.

Bowser, meanwhile,

did not wait long to tell of her incredible exploits. In fact, just days after

the fall of the Confederacy, Bowser, using her maiden name Mary Jane Richards,

began to teach former slaves in the area. In 1865, she traveled throughout the

country, giving lectures about her experiences at war under the name Richmonia

Richards.

The New York Times listed one such

event with the notice “Lecture by a Colored Lady,” which stated

“Miss RICHMONIA RICHARDS, recently from Richmond,

where she has been engaged in organizing schools for the freedmen, and has also

been connected with the secret service of our government, will give a

description of her adventures, on Monday evening, at the Abyssinian Baptist

Church, Waverley-place, near Sixth-avenue.”

Fittingly for a

former double agent, Richards’ speeches often contradicted one another, leaving

historians befuddled as to her actual story. One thing that remained

consistent, however, were reports of her sarcastic and humorous speaking

style. As Richards traveled the country, records of her whereabouts begin to

fade, in true spy fashion. She was last seen meeting abolitionist Harriet Beecher

Stowe in Georgia in 1867, sharing the riveting story of her life as

a spy yet again.

Slaves,

freedmen spied on South during Civil War

WASHINGTON — In the

Confederate circles he navigated, John Scobell was considered just another Mississippi

slave: singing, shuffling, illiterate and completely ignorant of the Civil War

going on around him.

Confederate officers

thought nothing of leaving important documents where Scobell could see them, or

discussing troop movements in front of him. Whom would he tell? Scobell was

only the butler, or the deckhand on a rebel sympathizer's steamboat, or the

field hand belting out Negro spirituals in a powerful baritone.

In reality, Scobell

was not a slave at all.

He was a spy sent by

the Union army, one of a few black operatives who quietly gathered information

in a high-stakes game of cat-and-mouse with Confederate spy-catchers and slave

masters who could kill them on the spot. These unsung Civil War heroes were

often successful, to the chagrin of Confederate leaders who never thought their

disregard for blacks living among them would become a major tactical weakness.

"The chief source of information to the

enemy," Gen. Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate

Army, said in May 1863, "is through

our negroes."

Little is known about

the black men and women who served as Union intelligence officers, other than

the fact that some were former slaves or servants who escaped from their

masters and others were Northerners who volunteered to pose as slaves to spy on

the Confederacy. There are scant references to their contributions in

historical records, mainly because Union spymasters destroyed documents to

shield them from Confederate soldiers and sympathizers during the war and

vengeful whites afterward.

"These kinds of spies and operatives come up over

and over again, many of them unnamed and rarely do they receive glory," said Hari Jones,

curator of the African

American Civil War Museum in Washington, who lectures on the Civil War's

African American spies.

Jones and other

experts are hoping the 150th anniversary of the Civil War will include some

measure of remembrance for these officers, some of whom are included in

exhibits at the African American Civil War Museum's new facility, which will

hold its grand opening on July 16-18.

Allan Pinkerton, head

of the Union Intelligence Service at the onset of the Civil War, detailed his

recruitment of black spies in his autobiography, including a couple of

successful missions by Scobell and the extraction of valuable papers from a

Union defector. Scobell in particular, Pinkerton said, was a "cool-headed, vigilant detective"

who easily duped the Confederates around him by assuming "the character of the light-hearted, happy darkey." Pinkerton

said.

"From the commencement of the war, I have found

the negroes of invaluable assistance and I never hesitated to employ them when

after investigation I found them to be intelligent and trustworthy,"

Harriet Tubman is the

most recognizable of these spies, sneaking down South repeatedly to gather

intelligence for the Union army while also leading runaway slaves to freedom

through the Underground Railroad. Often disguised as a field hand or poor farm

wife, she led several spy missions into South Carolina while directing others

from Union lines.

Another spy, Mary

Elizabeth Bowser, was born a slave to the Van Lew family, who freed her and

sent her to school. Bowser then returned to Richmond, where Elizabeth Van Lew

was running one of the war's most sophisticated spy rings.

Somehow, Van Lew got

Bowser a job inside the Confederate White House as a housekeeper. Bowser then

proceeded to sneak classified information out from under Confederate President

Jefferson Davis' nose.

According to the

memoirs of Thomas McGiven, the Union spymaster in Richmond whose cover was that

of a baker who delivered to the Confederate White House, Bowser

"had a photographic mind. Everything she saw on

the Rebel President's desk she could repeat word for word. Unlike most colored,

she could read and write. She made the point of always coming out to my wagon

when I made deliveries at the Davis' home to drop information."

Stories about Bowser,

who is also known as Ellen Bond, Mary Jones or Mary Jane Richards, show up as

early as May 1900 in Richmond newspapers, and her name was revealed in 1910 in

an interview with Van Lew's niece, according to Elizabeth Varon, author of a

book about Van Lew.

There is no proof

that Bowser existed beyond these recollections. Van Lew, like Pinkerton before

her, requested that Union forces turn over all her intelligence records at the

end of the Civil War and destroyed them, leaving no proof of her vast network.

Jefferson Davis'

wife, Varina, publicly denied that a black female spy could have infiltrated

their White House.

But Varon's book

suggests that Bowser's true name was Mary Richards, she survived the Civil War

and married a man named Garvin. Richards even writes in an 1867 letter that

during the Civil War she was "in the

service ... as a detective." Others are not as well-known.

Take, for example,

the three slaves who escaped the Confederate army on Morris Island, outside

Charleston, S.C., in 1863 and went to Union Brig. Gen. Q.A. Gillmore with

crucial information.

"They were officers' servants, and report, from

conversations of the officers there, that north and northwest faces of Fort

Sumter are nearly as badly breached as the gorge wall, and that many of our

projectiles passed through both walls, and that the fort contains no serviceable

guns,"

Gillmore said in a

report to his army superiors.

Using African

American troops, Gillmore later ordered the attack on Fort Sumter, which was

retaken by the North in February 1865, almost four years after the Civil War

began with the Confederates firing on the federal facility and taking it over.

One such informant

was Marie Louvestre (sometimes spelled Touvestre in historical records), a

former slave working for a Confederate engineer who was transforming the USS

Merrimac into the Virginia, the first Confederate ironclad warship. Realizing

the importance of her employer's breakthrough, Louvestre took some of the

paperwork, headed north and requested a private meeting with Navy Secretary

Gideon Wells.

The Union navy was

working on a similar ship, the USS Monitor. Louvestre, Wells said in an 1873

letter,

"told me the condition of the vessel, and took

from her clothing a paper, written by a mechanic who was working on the

`Merrimac,' describing the character of the work, its progress and probable

completion."

The Union navy

intensified its construction of the Monitor and sailed it down to Virginia,

leading to the world's first ironclad naval battle, a stalemate that kept the

rebel navy from breaking the federal blockade of Norfolk.

Union forces weren't

the only ones operating a black spy network in the South.

Black abolitionists

also ran a vast private network called the "Loyal League,"

"Lincoln's Legal Loyal League" or the "4Ls," which spied

for the North and spread word about the war among the black slaves. Scobell was

a member of the 4Ls, Pinkerton said, and used the network to get information to

Washington, D.C.

"I traveled to about the plantations within a

certain range, and got together small meetings in the cabins to tell the slaves

the great news. Some of these slaves in turn would find their way to still

other plantations — and so the story spread. We had to work in dead

secrecy," with "knocks and signs and passwords,"

said George

Washington Albright of Holly Springs, Miss., in 1937.

Utmost secrecy was

needed for these spies because of the consequences for those who were caught.

James Bowser, a free

black from Nansemond County, Va., decided to help the Union army by spying on

the South, according to Virginia Hayes Smith of Norfolk, Va., an elderly black

lady who related Bowser's story to Virginia Writers Project field interviewers

in 1937. Her recollections were subsequently published in the book

"Virginia Folk Legends."

Bowser's white

neighbors, some of whom coveted Bowser's farmland, heard rumors of his

activities, Smith said. A mob of planters attacked Bowser's house at night and

dragged out Bowser and his son.

"After severely beating both father and

son, the horde made Bowser lie on the ground and stretch his neck over a log

like a chicken on a chopping block," said Smith, "Then someone cut his head off. The plan was to kill the boy in the same

manner, but the more thoughtful ones disagreed. They suggested that he be left

to carry the news of this ghastly example back to the other Negroes. The mob

gave in."

Another Virginian, a

free black bricklayer named Martin Robinson, was killed on the spot.

Robinson was

considered "faithful and reliable"

by the Union hierarchy, and already had helped Union officers escape from the

infamous Libby Prison in Richmond, wrote Louis M. Boudrye, chaplain of the 5th

New York Calvary.

Union forces wanted

to attack Richmond in 1864 to free Union soldiers and spies held by

Confederates at Belle Isle, a small island in the middle of the James River.

Colonel Ulric Dahlgren was to cross the James River eight miles to the south

and press north into the city while other Union forces attacked from other

directions. Robinson, who lived in the area, was sent by the Bureau of Military

Intelligence to take Dahlgren's troops and horses to the best place to cross

the river.

When they arrived,

the river was impassable. Robinson panicked. Dahlgren decided Robinson had

deliberately deceived him. However, the river normally would have been passable

had it not been for flooding from heavy rains, Confederate veteran Richard G.

Crouch said in 1906.

"The colonel ordered him to be hung — a halter

strap was used for the purpose, and we left the miserable wretch hanging by the

roadside," Boudrye said.

How

Freedom Rider Diane Nash Risked Her Life to Desegregate the South

Now

an icon of the Civil Rights Movement, Nash was arrested dozens of times for

non-violent protests—including while six months pregnant.

“Diane, you’ve gotten

in with the wrong bunch.”

Those were

the words that civil rights activist Diane Nash

heard when her grandmother found out she was involved in the Civil

Rights Movement in 1960. Imagine her grandmother’s surprise when she found

out that Nash wasn’t just involved, but was leading the charge of the Nashville

student sit-ins. Later, in fact, she would go on to help coordinate the Freedom

Rides.

The

response of Nash’s family was one that many others would express throughout her

journey: fear. And with the violence and discrimination that was rampant

throughout the country in the 1950s and ‘60s, it’s easy to see why.

|

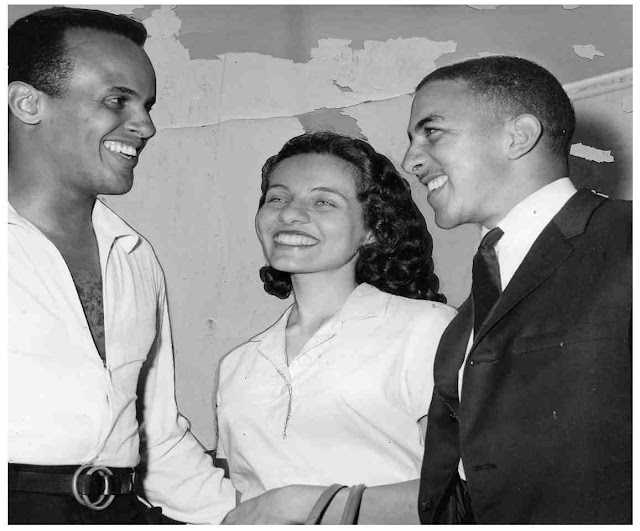

| Musician and actor Harry Belafonte with Freedom Riders Diane Nash and Charles Jones, discussing the Freedom Riders movement, 1961. Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images |

Nash was

born in 1938 and raised in Chicago, away from the strong racial divisions that

saw African Americans treated as second-class citizens under Jim Crow laws in the

South. It wasn’t until she enrolled at the historically black Fisk University

in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1959 that she came face-to-face with overt

discrimination.

“There were signs that said white, white-only,

colored. [The] library was segregated, the public library. Parks, swimming

pools, hotels, motels,”

she

recalls.

“I was at a period where I was interested in

expanding: going new places, seeing new things, meeting new people. So that

felt very confined and uncomfortable.”

|

| Diane Nash |

Among the

many facilities that weren’t available to Nash and her peers were restaurants

that served black customers only on a “takeout basis,” which meant they weren’t

allowed to sit and eat inside. Instead, black patrons were forced to eat along

the curbs and alleys of Nashville during the lunch hour.

Nash

couldn’t adhere to these rules. In her eyes, that would be agreeing with the

unjust laws. But before she could take a stand against these

restaurants—essentially protesting the government itself—she needed a plan of

action. Enter Jim Lawson, an activist who had studied Gandhi’s nonviolent

movement in India, and taught workshops on progress and change through

nonviolence at a Methodist church near the university.

The spring

after she enrolled at Fisk, just shy of 22 years old, Nash became a leader in

the Nashville Student Central Committee, which organized sit-ins at

discriminatory restaurants throughout the city. Faced with a fuming community

that did everything in their power to remove the students, Nash encountered the

frightening scenarios that she had prepared for during Lawson’s workshops.

Charles H. Percy, right, chairman of the platform committee of the Republican Party, speaking with Walter Bradford, Diane Nash, and Bernard Lee on July 20, 1960. AP Photo

Leading up

to her first sit-in, in February 1960, Nash worried about being arrested. She’d

voiced her concern in the workshops, saying that she’d help with phone calls

and organizing but in the end, she would not go to jail. “But when the time came, I went,” she says, of the dozens of

arrests she’d face in the not too distant future.

The success

of the sit-ins on May 10 that year would make Nashville the first southern city

to desegregate lunch counters in the country. But that was only the beginning

for the young activist.

The same

year, Nash traveled to Raleigh, North Carolina, to meet with other progressive

students in the South and form the Student Nonviolent

Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The organization would work with other major

organizations within the Civil Rights Movement, including the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Congress

of Racial Equality (CORE).

In 1961,

the Nashville Student Central Committee received a notice from CORE that they

were beginning the Freedom Rides,

a nonviolent protest to desegregate interstate bus travel and terminals that

started in Washington, D.C., before making its way through southern states. The

student activists offered to help in any way they could. It wouldn’t be long

before they were called on to fulfill that request.

As the

Freedom Rides went from one state to another, the participants found themselves

in increasing danger from angry communities vehemently against the idea of

integration. The aggression came to a head as the Freedom Rides reached

Alabama. The buses were burned and the activists beaten on May 14, 1961,

forcing them to retreat to New Orleans. From there, it was up to Nash to carry

the torch with a new group of Freedom Riders.

“We recognized that if the Freedom Ride was ended

right then after all that violence, southern white racists would think that

they could stop a project by inflicting enough violence on it,”

she says.

“And we wouldn’t have been able to have any kind of

movement for voting rights, for buses, public accommodations or anything after

that, without getting a lot of people killed first.”

So Nash and her peers continued the Freedom Rides, despite the objections of many powerful people, including Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Kennedy had instructed his assistant, John Seigenthaler, to speak directly with Nash in an attempt to call off the Freedom Rides. With so much bloodshed in Alabama, he urged the chairwoman to back down from the violence that undoubtedly awaited them on the trail.

“People understood very well what could happen,”

says Nash, who explained to Seigenthaler that the participants in the Freedom

Rides had given her sealed envelopes with their wills, in the event of their

deaths. “Fortunately, I was able to

return all those sealed envelopes.”

The Freedom

Rides concluded in the fall of 1961 with yet another victory for the Civil

Rights Movement; the Interstate Commerce Commission made segregated bus travel

and terminals illegal, effective November 1st. However, Nash’s strength would

again be tested when she faced law enforcement later that year. And this time,

she was pregnant.

In 1961,

Nash was arrested for “contributing to

the delinquency of minors” after encouraging young people to fight for

desegregated buses in Mississippi. At the time, she was living with her

husband, James Bevel, in Jackson. The couple, who met through

activism, had been spreading a message of nonviolence within the community.

Nash’s

attorney had wrongly advised her that she did not need to appear in court,

which resulted in a warrant for her arrest. Six months pregnant at the time,

Nash went to court to surrender to the authorities. She was facing a two-year

prison sentence.

“When I surrendered, I sat in the front seat of the courtroom and the bailiff told me to move back and I thought ‘I [might be here] for two years, I’m not moving anywhere,’” she says. “So they charged me with contempt of court for refusing to move to the back.”

The

contempt of court sentence lasted for 10 days. While in jail, the only thing on

Nash’s mind was her unborn child. She was determined to do everything she could

so that her child would enter a world that was equal for all Americans,

regardless of race.

After

serving out her sentence for contempt, the judge declined to hear Nash’s other

case. Nash believes the federal government tapped her telephone line and

listened in when she told organizations in the Civil Rights Movement that she

was pregnant and headed to jail for up to two years. On the heels of the

horrific imagery of the bloodied and beaten Freedom Riders that had been spread

far and wide, they surmised that Mississippi didn’t want to find itself, once

again, at the center of a national political debate.

As a

result, the government reduced Nash’s sentence for “contributing to the delinquency of minors” without formally

addressing it. This left Nash in a predicament. She didn’t want the prejudiced

justice system she had been fighting against to think that she was indebted to

it. She was ready and willing to serve her full sentence, after all.

“When I got home, I wrote Judge Moore a certified

return-receipt letter. I said, ‘In case you should change your mind and you

want me, here’s where you can reach me,’” Nash

recalls. And though the judge never took her up on the offer, Nash was always

ready to do what was necessary to make a mark. To change the world, she says

with a laugh, “sometimes you have to be

bad.”

Six

Unsung Heroines of the Civil Rights Movement

Below are a few of

the women who contributed to the fight for equal rights for Black American

women.

While their stories

may not be widely known, countless dedicated, courageous women were key

organizers and activists in the fight for Civil

Rights. Without these women, the struggle for equality would have never

been waged. “Women have been the backbone

of the whole civil rights movement,” activist Coretta Scott King

asserted in the magazine New Lady in 1966. Here are a few of their stories.

|

| Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray |

1. Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray (1910–1985)

Brandeis University professor Dr. Pauli Murray,

1970. (Credit: AP Photo)

The

Draftswoman of Civil Rights Victories

The writings of The

Rev. Dr. Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray were a cornerstone of Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, the 1954 Supreme Court case that ended school

segregation, but the lawyer, Episcopal priest, pioneering civil rights activist

and co-founder of the National Organization for Women wouldn’t be made aware of

that extraordinary accomplishment until a decade after the fact.

In 1944, Murray was

the only woman enrolled at Howard Law School—and at the top of her class. While

discussing Jim Crow laws, Murray had an idea. Why not challenge the “separate”

in “separate but equal” legal doctrine, (Plessy v. Ferguson) and argue that

segregation was unconstitutional? This theory became the basis of her 1950 book,

States’ Laws on Race and Color, which NAACP attorney Thurgood

Marshall called the “bible” of Brown

v. Board of Education.

In 1965, Murray and

Mary O. Eastwood co-authored the essay “Jane Crow and the Law,” which argued

that the Equal Protection Clause in the 14th

Amendment should be applied to sex discrimination as well. In 1971, a young

lawyer named Ruth

Bader Ginsburg successfully argued this point in Reed v. Reed in front of

the Supreme Court. Murray was named as a co-author on the brief.

Murray died in 1985,

and in the decades since, public awareness of her many contributions has only

continued to grow. Murray was sainted by the Episcopal Church in 2012, a

residential college at Yale was named in her honor in 2017, and she has become

an LGBTQ icon, thanks, in part, to the progressive approach to gender fluidity

that she personally expressed throughout her life. Despite all this, as she

wrote in the essay “The Liberation of Black Women” in 1970: “If anyone should ask a Negro woman in

America what has been her greatest achievement, her honest answer would be, ‘I

survived!’”

|

Mamie Bradley, mother of lynched teenager Emmett Till, crying as she recounts her son’s death, 1955. (Credit: Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images) |

2. Mamie Till Mobley (1921–2003)

Inspirational

Mother of a Martyr

Mamie Till Mobley’s

story is one of triumph in the face of tragedy. Though she never sought to be

an activist, her resolve inspired the civil rights movement and “broke the emotional chains of Jim Crow,” the

Rev. Jesse Jackson would remark upon her death.

On August 28, 1955,

Mobley’s 14-year-old son, Emmett

Till, was brutally murdered in Money, Mississippi, by two white men who

claimed that Till had “wolf-whistled” at one of their wives. When Till’s

mutilated corpse was found three days later in the Tallahatchie River,

Mississippi officials tried to dispose of the body quickly, but Mobley obtained

a court order to have her only child’s remains returned to Chicago. Though his

casket arrived padlocked and sealed with the state seal of Mississippi, Mobley

insisted that her son’s brutalized body be displayed during his funeral. “I want the world to see what they did to my

boy,” the

grieving mother explained.

“Mrs. Mobley did a profound strategic thing,” Jackson later told the New York Times. “More than 100,000 people saw his body lying in that casket…at that time

the largest single civil rights demonstration in American history.” Until

her death in 2003, at the age of 81, Mobley advocated for underprivileged

children and against racial injustice. Although she never got justice for her

son (his murderers were acquitted by an all-white male jury), Mobley didn’t let

it dampen her spirit. As she told a reporter: “I have

not spent one minute hating.”

|

Bronx resident Claudette Colvin in 2009. (Credit: Julie Jacobson/AP Photo) |

3. Claudette Colvin (born 1939)

The Teenager Who Refused to Give Up Her Bus Seat Before Rosa Parks

When

Claudette Colvin‘s high school in Montgomery, Alabama,

observed Negro History Week in 1955, the 15-year-old had no way of knowing how

the stories of black freedom fighters would soon impact her life. “I knew I had to do something,” she later

told USA Today. “I just didn’t know where

or when.”

Colvin

got her chance on March 2, 1955, when she boarded a bus in downtown Montgomery.

She and three other black students were told to give up their seats for a white

woman. Colvin, emboldened by her history lessons, refused. “My head was just too full of black history,” she stated in an interview with NPR.

“It felt like Sojourner

Truth was on one side pushing me down, and Harriet

Tubman was on the other side of me pushing me down. I couldn’t get up.”

Colvin

was arrested and eventually put on indefinite probation. Though Colvin’s

courageous act occurred nine months before Rosa Parks’

similar protest, the NAACP chose to use the 42-year-old civil rights activist

as the public face of the Montgomery bus boycott, as they believed an unwed

mother—Colvin became pregnant when she was 16—would not be the best face for

the movement. Colvin felt slighted, but later joined three other women—Mary

Louise Smith, Aurelia Browder and Susie McDonald—as the plaintiffs in Browder

v. Gayle, the case that ultimately overturned bus segregation in Alabama.

Colvin

rarely talked about her heroic actions until the 1990s. “I’d like my grandchildren,” she said, “to be able to see that their grandmother stood up for something, a

long time ago.”

4. Maude Ballou (1925-2019)

In 1955, Maude

Ballou—a young mother who had studied business and literature in college and

was program director of the first black radio station in Montgomery,

Alabama—was approached by her husband’s friend, a young minister and activist

named Martin

Luther King, Jr., to be the personal secretary.

After agreeing,

Ballou became the Rev. Dr. King’s right-hand woman from 1955 until 1960, years

of great unrest and transforming events that included the Montgomery

Bus Boycott, the publication of King’s first book, Stride Towards Freedom,

and the Prayer Pilgrimage for Peace in Washington, D.C.

Her work placed

Ballou in enormous danger. In 1957, she was listed as number 21 on the Montgomery

Improvement Associations list of “persons

and churches most vulnerable to violent attacks.” (King was at the top of

the list.) Her children’s lives were threatened, and KKK members watched her at

work through the windows of the church. But Ballou just kept on working. “I was a daredevil, I guess,” she told The Washington Post in 2015.

“I didn’t have time to worry about what might happen,

or what had happened, or what would happen,” said Ballou, who went on to serve as a teacher and college

administrator. “We were very busy doing things, knowing that anything could

happen, and we just kept going.”

Ballou passed away on

August 26, 2019. She was 93 years old.

|

| Diane Nash at the 2011 Search For Common Ground Awards at the Carnegie Institution for Science, 2011. (Credit: Leigh Vogel/Getty Images) |

5. Diane Nash (born 1938)

Freedom Rider and

Nonviolent Student Activist for Desegregation

A native of Chicago,

Diane Nash hadn’t experienced the shock of desegregation within the Jim Crow

South until she attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. The “Whites

Only” signs scattered throughout Nashville inspired Nash to become the

chairperson of the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee (SNCC) in 1960,

where she organized sit-ins at segregated lunch counters throughout Nashville.

Nash kept the group’s commitment to nonviolence front and center at the

sit-ins, which proved very effective in ending the discriminatory practices

within the restaurants.

The following year,

Nash took over responsibility for the Freedom Rides, a protest against

segregated bus terminals that took place on Greyhound buses from Washington

D.C. to Virginia. The Freedom Rides, which were initially organized by the

Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), encountered a mob of angry segregationists

as they entered Anniston, Alabama, and were brutally beaten and unable to

finish the route. SNCC—under the direction of Nash— continued the protest from

Birmingham, Alabama, to Jackson, Mississippi.

Before setting off

with a group of 10 students from Nashville, Nash received a call from John

Seigenthaler, assistant to Attorney General Robert Kennedy Jr., who tried to

persuade her to end the Freedom Rides, insisting the bloodshed would only

continue if they persisted. Nash, unshaken by the stance of the White House,

told Seigenthaler that they knew the risks involved and had already prepared

their wills before continuing the Freedom Rides.

Nash later moved back

to Chicago and went on to serve as an advocate for fair housing practices. Her

contributions to the success of Civil Rights movement have been increasingly

recognized in the years since. In 1995, historian David Halberstam described Nash

as “bright, focused, utterly fearless,

with an unerring instinct for the correct tactical move at each increment of

the crisis.”

6. Coretta Scott King (1927–2006)

Human Rights Activist, Pacifist, Musician

In 1968, just days

after the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., his wife, Coretta

Scott King, took his place at a sanitation workers’ protest in Memphis. A few

weeks later, she kicked off his planned Poor People Campaign. She had long been

politically active, but her husband’s death galvanized her activism.

King earned a

bachelor’s degree in Music and Education from Antioch College, and had met her

future husband while studying at the New England Conservatory of Music in

Boston. In the early years of the civil rights movement, she hosted a series of

popular “Freedom Concerts,” raising thousands of dollars for the movement.

After her husband’s

assassination, King campaigned tirelessly to make his birthday a national

holiday, and raised millions to establish the Martin Luther King, Jr.

Center for Nonviolent Social Change. An avowed feminist, she was active in

the National Organization for Women, and was an early advocate for LBGTQ

rights. During the 1980s, she was a vigorous opponent of apartheid.

King understood that

she would be remembered as a widow and human rights activist, but, as she once said, she hoped to be thought of a

different way:

“as a complex, three-dimensional, flesh-and-blood

human being with a rich storehouse of experiences, much like everyone else, yet

unique in my own way…much like everyone else.”

|

| John Lewis 'good trouble' |

‘Good

Trouble’: How John Lewis and Other Civil Rights Crusaders Expected Arrests

John

Lewis was arrested 40 times during the civil rights movement.

Activists who

practiced civil disobedience in the 1960s knew their opponents wouldn’t show them

civility in return. Congressman John Lewis, a leader of the civil rights

movement who co-founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was arrested 40 times between 1960 and 1966 for protesting

racist laws and practices in the Jim Crow South. During the first attempt to

march from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights on March 7, 1965, state

troopers and “deputized” white men beat him so badly they fractured his skull.

Lewis, who died on

July 17, 2020 at age 80, often spoke of what he called “good trouble.” Getting

arrested for trying to march across Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge—which bears

the name of a Ku Klux Klan leader—was an example of this. Speaking atop the

same bridge 55 years after the events of that day, known as “Bloody Sunday,” he

urged listeners to “get in good

trouble, necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America.”

The Greensboro Lunch Counter Sit-Ins

Lewis’ first arrest

was during a lunch counter sit-in in 1960. On February 1 of that year, four

Black college students had sat at a “whites-only” lunch counter at a

Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina. As expected, the staff refused to

serve them; but the students refused to leave. They remained in their seats and

stayed until closing. The next day, they came back with more students to do it

again.

The Greensboro

sit-ins sparked a wave of similar protests in which students protested lunch

counters’ racist policies by publicly violating them. Lewis, Diane Nash and

other members of the Nashville Student Movement began organizing sit-ins in

their city. On February 27, Lewis sat at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in

Nashville where angry white patrons beat him and his fellow protestors and tried

to pull them off their seats. When the police arrived, it was the protestors,

not the attackers, whom they arrested. This was 20-year-old Lewis’ first arrest.

“I didn't necessarily want to go to jail,” he recalled in a 1973

interview for the Southern Oral History Program.

“But we knew…it would help solidify the student

community and the Black community as a whole. The student community did rally.

The people heard that we had been arrested and before the end of the day, five

hundred students made it into the downtown area to occupy other stores and

restaurants. At the end of the day ninety-eight of us were in jail.”

The pressure worked:

That spring, lunch counters in Nashville began serving Black customers.

The Freedom Riders

The next year,

student activists traveled through the south on public buses to protest the

federal government’s refusal to enforce the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1960 ruling in

Boynton v. Virginia that segregated public transportation was

unconstitutional. Lewis was one of the original 13 Freedom

Riders who started off on May 4, 1961 in Washington, D.C. Many more joined

the trip or started their own Freedom Rides that summer. One of those who

joined was Lewis’ fellow Nashville activist Reverend

C.T. Vivian, who died at age 95 on July 17, 2020, the same day as Lewis.

The first violent

attack on the Freedom Riders came only five days into their journey, when Lewis

attempted to enter the “white” waiting room in the Greyhound terminal in Rock

Hill, South Carolina. A group of angry white men beat up Lewis and two other

Freedom Riders. On May 14, a white mob in Anniston, Alabama set fire to

a bus carrying nine Freedom Riders and then beat up the passengers.

White mobs continued

to attack Freedom Riders in Birmingham, where the city’s police commissioner

arrested Lewis and his fellow riders. Afterward, the commissioner drove them to

a remote area near the Tennessee border known for Klan terrrorism and left them

there. In Jackson, Mississippi, police officers arrested Lewis, Vivian and

other Freedom Riders, sending them to Parchman Farm. At the infamously brutal

state penitentiary, guards beat them and forced them to work on the

penitentiary’s massive farm without pay.

Once again, the

arrests drew national attention—as activists hoped they would—putting pressure

on officials to act. That fall, the Interstate Commerce Commission finally enforced Boynton v. Virginia by demanding

that interstate bus services integrate their bus seating and terminals.

The Legacy of ‘Good Trouble’

After the Freedom

Rides, Lewis continued to play a key role in the civil rights movement. In June

1963 he became the chairman of SNCC. The next month, he was the youngest

speaker at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

“We are tired of being beaten by policemen,” he told the crowd from the Lincoln Memorial.

“We are tired of seeing our people locked up in

jail over and over again. And then you holler, ‘Be patient.’ How long can we be

patient? We want our freedom and we want it now. We do not want to go to jail.

But we will go to jail if this is the price we must pay for love, brotherhood,

and true peace.”

For the 50th

anniversary of Bloody Sunday, Lewis “live-tweeted” the day as he’d experienced

it. “I was hit in the head by a state

trooper with a nightstick. My legs went out from under me,” he wrote. “I thought

I saw death. I thought I was going to die.” TV stations broadcast the

violent footage around the country in 1965, pressuring the government to act by

passing the Voting Rights Act later that year.

In 1987, Lewis became

a U.S. Congressman, representing Georgia’s 5th District in the U.S. House of

Representatives. He held the position until his death in 2020. Yet even as a

Congressman, he continued to get into what he called “good trouble.” His last

arrest was on October 8, 2013. Posting a picture of it online, he tweeted: “Arrest

number 45, protesting in support of comprehensive immigration reform.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please submit your comments below