This is such an excellent article by Aly

Renwick of Veterans for Peace (UK) that I just had to publish it. It deserves a much wider hearing.

For me what is interesting is the connection

between Ireland and Palestine. As the article quite correctly says, the hated

Black and Tans, when they were finished with Ireland were promptly sent to Palestine

to repress Arab nationalism. In the words of the first Military Governor of Jerusalem,

Sir Ronald Storrs (Orientations) A Jewish

State will be for England a little, loyal Ulster in a sea of potentially

hostile Arabism.’

The links between Ireland and Palestine are symbolised in the figures of Winston Churchill and Lloyd George. Churchill was the Colonial Secretary who presided over Partition in Ireland and the implementation of the Mandate in Palestine. Lloyd George, who welcomed Hitler to power in 1933, was the Prime Minister who presided over the negotiations that led to Partition, threatening the whole of Ireland with unparalleled violence unless the Irish delegation to Britain gave way. Michael Collins reluctantly accepted partition and was soon after assassinated.

The connections between a Protestant settler

state in the North of Ireland and a Jewish state in Palestine were immediate

and obvious to British imperialism. In both states settlers dependant on British

firepower, created their own society amidst the indigenous population – Irish Catholics

and Palestinian Arabs. In Ireland an artificial majority was created by

confining the Ulster statelet to the 6 Counties. In Palestine the Zionists used

the simple expedient of expelling the majority of the population. In both cases

a combination of ethnic cleansing and partition achieved the objectives of

imperialism. Divide and rule paid

handsome dividends, whether it was in Palestine, Ireland or India and in all

three countries it was achieved with massive bloodshed.

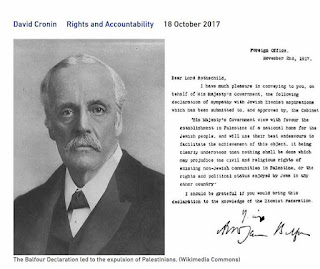

On November 2nd 1917 British

imperialism promised the land of the Palestinians to the Zionist settlers,

despite the fact that it was not theirs. The document encompassing this

strategy was the Balfour

Declaration named after the then Foreign Secretary Arthur J Balfour. In

1905 as Prime Minister he had introduced the Aliens Act aimed at keeping Jewish

refugees out of Britain. Balfour combined in himself both anti-Semitism and Zionism,

which is a combination that has reared its head repeatedly since then.

Balfour first saw service in Ireland where he

was known as ‘Bloody Balfour’. From 1887 to 1891, Balfour headed

Britain’s administration in Ireland. On his appointment to that post, Balfour

proposed to combine repression and reform.

The repression he advocated should be as “stern” as that of Oliver

Cromwell, the English leader who invaded Ireland in 1649. Cromwell’s troops are

reviled in Ireland for the massacres

they carried out in the towns of Wexford and Drogheda.

Siding with the gentry against what he called the “excitable peasantry,” Balfour prioritized repression over reform.

When a rent strike was called in 1887, Balfour authorized the use of

heavy-handed tactics against alleged agitators.

Three people died after police fired

on a political protest in Mitchelstown, County Cork. The incident earned him

the nickname of “Bloody Balfour.” [see The

racist worldview of Arthur Balfour by David Cronin].

We also see, in both colonies, how resistance to British colonialism was criminalised. The use of paramilitary police was used to reinforce this. In other words the natives weren't rebelling against the British, it was simply 'criminal elements' amongst them who objected to British policies of exploitation and starvation. The Nazis also termed their opponents 'bandits' and sought reprisals against innocent civilians and hostages. No one should think that Nazi imperialism in Eastern Europe was that different from the horrors of European imperialism in its mindset.

Which was

why, when Ireland’s Fine Gael Party, descended from those in the South who

supported the British, intended to commemorate the Royal Irish Constabulary

there were protests and boycotts and eventuall Leo Varadkar, the Taoiseach was forced

to call the whole thing off although he still defended

his decision to honour these murderers and rapists. That might be why Varadkar

polled fewer votes than Sinn Fein in his constituency.

The article below is excellent. It puts British policing into

context. Although based on consensus it

always has at its back, as we saw in the 1984-5

Miners’ Strike, the armed fist in a velvet glove. There were repeated reports in 1984-5 that

soldiers were present dressed as police. Then the power of the state and the

magistrates and judges all bent over backwards to help defeat the state.

In other words the capitalist state is not and never has been neutral. It is a lesson that socialists inside and

outside the Labour Party need to take to heart. The Police are not your friends

and aren’t neutral. It is the question of the state that divides socialists

from social democrats.

Tony Greenstein

COLONIAL POLICING by Aly Renwick

Last year, in 2019, there was in Britain a considerable amount of media

coverage of the anti-government protests in Hong Kong. Usually the protesters

were praised, while the police who faced them were criticised as oppressive,

but fifty-two years before, in 1967, there had been similar protests and

repression. At that time, however, Hong Kong was run as a British colony and

then it was the protesters who were condemned and the police who were praised.

Hong Kong Island was ceded to Britain after the First Opium War in 1842

and the Hong Kong Police Force was established two years later, with upholding

British control as its main task. In 1966 a number of labour disputes escalated

into large-scale protests against British colonial rule, which lasted throughout

the next year and, after 51 deaths and over 800 injured, a number of social

reforms were introduced and the protests gradually ended. Two years later, for

their role in curbing the protests, Queen Elizabeth bestowed the ‘Royal’ title

on the police – making them the Royal Hong Kong Police Force (RHKPF).

From Tudor times the state in Britain had gradually been constructed

into a fiscal system capable of financing the building of an empire on a world

scale. Later, global profiteering, including the slave trade and going to war

to force drugs (opium) on China – aligned with commerce and taxes, especially

on income – provided the surplus money that financed the technological advances

of the industrial revolution and led to the expansion of the British Empire.

Adam Smith’s ‘The Wealth of Nations’, published in 1776, had argued for

a policy of government non-interference in economic affairs and for giving free

rein to the ‘magic hand of the market’, which was to be applied ruthlessly both

at home and abroad. The administration of government, centred in Whitehall

since the 16th century, was modernised after the Northcote-Trevelyan Report of

1845, which extensively increased the number of civil service mandarins and

their departments.

In Britain and Ireland, the suppression of the democratic ideals thrown

up by the French Revolution had culminated in the defeat of the United

Irishmen. On the first of January 1801 the 500 year-old Irish parliament was

dissolved and the Act of Union came into effect. A new flag, the Union Jack,

was unfurled – which added the cross of Saint Patrick to those of Saint George

and Saint Andrew. The Armed Forces of Britain would take this new symbol of

empire to the far corners of the world, as they were used in a long series of

engagements to extend the boundaries of British control.

The moves toward a laissez-faire (market-led and regulation-free pure

capitalism) economic policy led to the Reform Acts, from 1832, which

consolidated the hold of private enterprise over parliament, strengthening the

middle class and gave ever-increasing power to the entrepreneurs. In Britain

the rural poor and Irish emigrants, flocking into the greatly expanding

industrial cities, worked long hours on starvation wages to facilitate the

factories prolific output:

Divide and

rule, both in Britain and overseas, was used to keep the masses divided and,

while the rulers exploited cheap labour at home, plunder, combined with trade

monopolies, became the order of the day abroad. At the height of the Empire,

Britain, a small island, was ruling nearly a quarter of the world’s land

surface and populations numbered in their hundreds of millions. Therefore, a

system of enforcing control was initiated that was to include, not only the

Army and Navy, but also a local force of colonial armed police – that later

would include in Hong Kong the RHKPF.

The Testing Ground

Ireland, as

was often the case, became the testing ground for this type of repressive rule

and in 1812, Sir Robert Peel, after being appointed the Chief Secretary of

Ireland, arrived in Dublin. At that time all of Ireland was a part of the

United Kingdom, but there were frequent political protests and actions. Unlike

Scotland and Wales, Ireland had never accepted English rule, or its

incorporation into the UK, and the country was filled with barracks full of

British soldiers.

Peel, a

devotee of markets and the Empire, had become an MP in 1809 during the Napoleonic

Wars, which were to end with the battle of Waterloo in 1815. Four years later,

the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester, saw voices for a more democratic society

at home repressed. Peel was also a supporter of law and order having served

part-time as a captain in the Manchester Regiment of Militia in 1808.

In Ireland

the Army’s direct use of brute force was often proving to be counter-productive

and hard to explain away. The troops were anyway continually required for wars

in far off places and all this suggested that a new ‘policing force’, mainly

drawn from the indigenous population, was required. An armed constabulary,

which like the army would operate from fortified buildings and be under central

control, but one that would be precise, disciplined and more politically

acceptable than soldiers.

As

communications improved, the truth was becoming harder to hide and greater

efforts were required to provide explanations for the seemingly never-ending

outbreaks of anti-government violence in Ireland. The British authorities, who

were attempting to attribute all violent acts to ‘bandits’ and ‘outlaws’,

considered that making a constabulary the prime upholders of ‘law and order’,

rather than the army, could help to maintain this fiction. And therefore

diminish potentially embarrassing political protests to issues of crime and

criminality.

Peel, who

was later to become the UK’s Prime Minister first in 1834/5 and again in

1841/6, initiated the first police service in both Ireland and England. There

were, however, major differences in the set-up and running of the constabulary

in each country. In Ireland Peel advocated setting up a countrywide police

force and two years later the Peace Preservation Force was used for the first

time in Middlethird, County Tipperary.

A county

constabulary was later added, but the two forces were amalgamated as the Irish

Constabulary (IC) in 1836 and brought under central control. Throughout this

period, political developments often followed a familiar path, as

constitutional politicians like O’Connell and Parnell waged campaigns for land

reform and national rights. When peaceful requests, then protests, came up

against a wall of hostility, intransigence and repression from the landlords

and the British establishment, underground movements like the Young Irelanders

and the Fenians emerged to carry on the struggle by violent means.

In 1867

Queen Victoria granted that the prefix ‘Royal’ be added to the name of the

Irish Constabulary in recognition of the part the force had played in suppressing

the Fenian movement:

‘For the Irish Constabulary, the

Fenian uprising brought them unparalleled fame … In Adam’s Police Encyclopaedia

the author had this to say: “On Friday, September 6, 1867, at the Constabulary

Depot in Phoenix Park, in the presence of the Lord Lieutenant, the Marchioness

(afterwards Duchess) of Abercorn attached with her own hands the medals, which

were specially struck for the occasion, upon the breasts of those who had

specially distinguished themselves. In addition to a medal some were given a

sum of money, or a chevron” … Her majesty was “graciously pleased to command”

that the force “be hereafter called the Royal Irish Constabulary” and “that

they shall be entitled to have the harp and crown as badges of the force”.’ [The Irish Police,

by Séamus Breathnach, Anvil Books 1974].

Operating

from fortifications and under strict central control, the Royal Irish

Constabulary (RIC) was developed as an armed coercive force furnishing the

public face of colonial authority:

‘The RIC was from its outset to

be controlled by Irish Protestants. It was responsible to the Irish authorities

in Dublin who were Protestants or Anglo-Irish. Presumed to be the RIC’s chief

challengers were Irish nationalists – mostly (though eventually not

exclusively) Catholic – that is, not criminals but political militants.

By making control of Irish

nationalism a police rather than a military affair, officials in Dublin and

London could relegate the nationalists to the category of mere “bandits”. The

challenge to state security could thus be understated. The use of “bandits” to

describe insurgents so long as they were a matter for the police, became

conventional in many British colonies which adopted the RIC model…’ [Ethnic

Soldiers, by Cynthia H Enloe, Penguin Books 1980].

The Police

in England

In 1829,

after Peel had moved back to Westminster to become the Home Secretary, he

initiated a Metropolitan Police force for London. And from the capital of the

Empire, ‘British democracy’ was manifested as the model for any legitimate

government. The ruling class, however, sought to maintain their dominance at

home and abroad, so there was a crucial difference in Britain and Ireland

between the ‘force and consent’ (using Gramsci’s characterization) needed to establish

the ruler’s hegemony – and consequently how ‘law and order’ was applied.

Inside

Britain, while the establishment ensured their interests predominated,

Westminster promoted the concept that the state forces were neutral and acted

in the interests of all the people. In fact, dissident voices and actions were

categorised as being against the ‘national interests’ and ignored or crushed,

but as the ruling elite established their dominance and authority, they did

create a cohesive state system which most people gradually adhered to.

Following

this pattern, the police in Britain developed as an area-based unarmed force

which sought the consent of the people among whom they operated. There was a

measure of local control over the police, who carried truncheons instead of

firearms and whose main task became the prevention of crime (law). In the

background were units like the Special Branch – initially formed in 1883 to

combat Fenian bombings – and other paramilitary units with access to arms,

whose main task was upholding the status-quo (order).

In Ireland,

where the legitimacy of British rule was always suspect and never carried the

moral authority of state rule back home, the emphasis between force and consent

was very much the other way around. The RIC were centrally controlled, armed

and acted mainly as a repressive force upholding British rule (order), with the

prevention of crime (law) a secondary role.

In 1839, a

Commission of Inquiry was looking into the setting up of a police force for

England and Wales. After examining the police in Ireland the commission

reported that:

‘The Irish constabulary force is

in its origination and action essentially inapplicable to England and Wales. It

partakes more of the character of a military and repressive force, and is consequently

required to act in greater numbers than the description of force which we

consider the most applicable, as a preventive force …’ [First

Report of the Commissioners appointed to inquire as to the best Means of

Establishing an Efficient Constabulary Force in the Counties of England and

Wales, 1839].

Views of Colonial Policing

In Ireland,

the IC / RIC were recruited from areas outside of the populace they patrolled

and they had more than double the numbers of personnel for the density of

population than police forces in England. In 1847 an army veteran, Alexander

Somerville, who had been flogged for writing a ‘seditious letter’ to a

newspaper while serving with the Scots Greys, visited Ireland. Somerville, who

came from a poor working class background, was especially incensed by the

landlords:

‘A large number of the worst

Irish landlords, Somerville believed, had “brought Ireland to a condition

unparalleled in the history of nations.” As a class, he thought that they stood

“at the very bottom of the scale of honest and honourable men.” Indeed, “the

Irish landlord is only a rent eater, and his agent a rent-extractor, neither of

them adding to the resources of the farm – not even making roads or erecting

buildings”. While in England, rural depopulation was said to be due to the

attractions of urban industrial employment, in Ireland such employment was

unavailable, and “clearances” were forced, coercive and intolerable. Somerville

complained of how the present time was an opportunistic one for evictions: “We

have England paying out of English taxes all those armed men, and providing

them with bullets, bayonets, swords, guns and gunpowder, to unhouse and turn to

the frosts of February those tenants and their families”.’ [Letters

from Ireland during the Famine of 1847, by Alexander Somerville – edited by K.

D. M. Snell, Irish Academic Press 1994].

Somerville,

noting that many of these armed men were police, wrote that:

‘One of the

first things which attracts the eye of a stranger in Ireland … and makes him halt

in his steps and turn round and look, is the police whom he meets in every part

of the island, on every road, in every village, even on the farm land, and on

the seashore, and on the little islands which lie out in the sea.’ Somerville

continued:

‘These

policemen wear a dark green uniform and are armed; this is what makes them

remarkable, armed from the heel to the head. They have belts and pouches, ball

cartridges in the pouches, short guns called carbines, and bayonets, and

pistols, and swords.’ [Letters from Ireland during the Famine of 1847, by

Alexander Somerville – edited by K. D. M. Snell, Irish Academic Press 1994].

1.

Garrow Green, an RIC cadet, wrote about his

training and explained how it was like being in an army unit:

‘To readers unacquainted with the

corps, I may say that it is a military police peculiar to Ireland, and

officered in much the same way as the Army … I may say that the Royal Irish

Constabulary Depot differs in no respect from an army infantry barracks …’ [In the

Royal Irish Constabulary, by G. Garrow Green, Dublin 1905].

Continually

fed information from a network of spies and informers the IC / RIC used this

intelligence – combined with their local knowledge, which they augmented during

policing (law) – to great effect during counter-insurgency offensives (order)

against political opponents:

‘The fact is that the really

effective influence upon the development of the colonial police forces during

the nineteenth century was not that of the police in Great Britain, but that of

the Royal Irish Constabulary … From the point of view of the colonies there was

much attraction in an arrangement which provided what we should now call a

“paramilitary” organisation or gendarmerie armed and trained to operate as an

agent of the … government in a country where the population was predominantly

rural, communications were poor, social conditions were largely primitive, and

the recourse to violence by members of the public who were “against the

government” was not infrequent. It was natural that such a force, rather than

one organised on the lines of the purely civilian and localised forces of Great

Britain, should have been taken as a suitable model for adaptation to colonial

conditions.’ [The Colonial Police, by Sir Charles Jefferies, Max Parrish 1952].

Army Barracks, Police Forts & Famine

Throughout

the nineteenth century there were barracks for British soldiers all over

Ireland. Fermoy, built overlooking the Blackwater River in County Cork, was a

huge barracks around which the town was built to service it. The largest

garrison, the Curragh, was first established in 1646, built on a large plain

near Kildare, the barracks occupied one side of the Dublin road with the

race-track on the other.

Ireland

became crisscrossed with large army barracks situated at strategic locations,

and the smaller, but much more numerous, fortified buildings of the police.

During the period of the famine there were 1,600 fortified IC bases throughout

the country, situated in villages, towns and cities. Backed by soldiers when necessary,

armed IC men assisted in enforcing evictions, protected landlords and their

agents, and guarded the foodstuffs that were still being shipped abroad for

profit.

An extensive

prison network was also constructed, as the system of transporting prisoners

was ending and by the time of the famine 26 new prisons had been built to

augment the 18 already in existence. In these buildings political prisoners,

especially, faced a harsh regime of control, punishments and forced-labour. In

1856, Frederick Engels visited Dublin and gave his view of the country:

‘Ireland may be regarded as

England’s first colony … the so-called liberty of the English citizen is based

on the oppression of the colonies. I have never seen so many gendarmes in any

country and the sodden look of the Prussian gendarme is developed to its

highest perfection here amongst the constabulary, who are armed with carbines,

bayonets and handcuffs.’

Thirty years

later, in 1887, the poet Francis Adams also visited Dublin and recorded this

image of the city in his poem: ‘Dublin At Dawn’:

In the chill

grey summer dawn-light

We pass through the empty streets;

The rattling wheels are all silent;

No friend his fellow greets.

We pass through the empty streets;

The rattling wheels are all silent;

No friend his fellow greets.

Here and

there, at corners,

A man in a great-coat stands;

A bayonet hangs by his side, and

A rifle is in his hands.

A man in a great-coat stands;

A bayonet hangs by his side, and

A rifle is in his hands.

This is a

conquered city,

It speaks of war not peace;

And that’s one of the English soldiers

The English call “police”.

It speaks of war not peace;

And that’s one of the English soldiers

The English call “police”.

Throughout

the British Empire there were corrupt and immoral political system and coercive

rule. In both India and Ireland there were famines, brought on by the strident

use of a market-led economic policy – during which the use of Colonial Police

allowed acts of political protest to be depicted as ‘crime’. As over a million

Irish people were dying from starvation and subsequent diseases, ships still

left Irish ports laden with meat, flour, wheat, oats and barley – to sell for

great profits on the market.

This pattern

of the army, acting as back-up to a paramilitary police force, became the

prototype for maintaining British rule in other parts of the Empire. Sir Robert

Peel, who instigated the first police forces in Ireland and Britain, was later

the British Prime Minister at the start of the Famine and the starving Irish

people who received the attentions of Britain’s armed forces made little

distinction between his police, who they called ‘Peelers’, and British

soldiers. The nationalist leader Daniel O’Connell called him ‘Orange Peel’ and

commented that Peel’s smile was ‘like the silver plate on a coffin.’

The Market & Coercive Policing

Located just

a narrow strip of water away, it was inevitable that Ireland would become an

early victim to English expansionism. While land and exploitation were the main

motive behind the drive to subdue the Irish, there was also a second reason. In

the past, O’Neill and Tone had forged links with England’s enemies, Spain and

France, who had both landed troops in Ireland. This had fuelled England’s

determination to subdue and control Ireland, to ensure it could never again

pose a military threat.

William

Cobbett, an ex-army sergeant-major, also thought that Britain’s security should

be protected, but he knew that the use of repressive laws and military might in

Ireland was wrong and counterproductive. He believed that ‘a real union of the

hearts’ could be achieved between the people of Britain and Ireland if reason

was used instead of force:

‘It is not by bullets and

bayonets that I should recommend the attempt to be made, but by conciliation,

by employing means suited to enlighten the Irish people respecting their rights

and duties, and by conceding to them those privileges which, in common with all

mankind, they have a natural and legitimate right to enjoy.’

[Not by Bullets and Bayonets – Cobbett’s Writings

on the Irish Question 1795-1835, by Molly Townsend, Sheed and Ward Ltd 1983].

Cobbett,

after leaving the British Army, had become a leading voice against injustice

and for reform:

Cobbett’s

appeals about Ireland fell on deaf ears and even a tragedy like the famine

brought no change in policy. In 1846, a new Coercion Act designed to control

possible insurrection by the starving Irish people was enacted. It was the

eighteenth Coercion Act to be brought in since the 1801 Act of Union. As Lord

Brougham remarked, the new bill: ‘Possessed

a superior degree of severity’.

Pro-imperialist

historians often brag that, at its height, the British Empire covered a quarter

of the world’s land surface and contained a population of over 400 million.

They neglect to tell us, however, that it was drug trafficking and the slave

trade that helped put the ‘Great’ into Great Britain; or that the famines in

Ireland and India, which caused millions of deaths, were the result of official

callousness and subjugation, during the application of an unyielding political

and economic ideology.

Under the oppressive

control exercised through Britain’s Armed Forces and centrally controlled

colonial Police Forces, profits had multiplied in the City of London during the

Victorian heyday of the British Empire. While at home and abroad many ordinary

people faced slavery, misery, starvation and death.

The Veterans of WW1

The last

days of the Victorian era had seen Britain’s standing, as the premier world

power, starting to decline – and it was the resulting rivalry between the core

capitalist nations that led to two world wars. All over Europe, at the end of

WW1, there were young men who had gone straight into the trenches and who knew

no life save that of soldiers. Most of these demobbed veterans had served at

the front and many of these men were left traumatised and brutalised by their

experiences.

In Germany,

some of these disillusioned veterans were recruited into the anti-revolutionary

Freikorps (Free Corps) by their former officers, who now used these ex-soldiers

to help crush the political left:

George L.

Mosse, a Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin, wrote about these

WW1 veterans:

‘There was no doubt a

ruthlessness, a feeling of desperation, about some of these men who were unable

to formulate effective political goals and who rightly or wrongly thought

themselves abandoned by the nation whose cause they championed. The suppression

of revolution in Berlin or Munich was accompanied by brutal murders, and such

murders continued even after the Free Corps had been disbanded, most often

committed by former members of the corps. … The 324 political assassinations

committed by the political Right between 1919 and 1923 (as against twenty-two

committed by the extreme Left) were, for the most part, executed by former

soldiers at the command of their one-time officers…’

[Fallen Soldiers, by George L Mosse, Oxford

University Press 1990].

These

veteran ‘new men’ saw themselves as continuing the comradeship established

among the fighting men at the front. In Germany many demobbed veterans were

later to join the Nazi Brownshirts of Hitler, himself a WW1 veteran. In Italy

they marched on Rome with Mussolini and in Russia they fought on both sides in

the civil war.

In 1916,

during WW1, British Army firing squads had been busy in Ireland after

frustrated Nationalists in Dublin had rebelled against British rule. Martial

law was declared, the Easter Rising was crushed and military courts-martial

sentenced 15 of the Irish leaders, including Pearse and Connolly, to be shot.

Many of the other prisoners were deported to Britain and confined in special

prison camps.

After the

ending of WW1, in India and Ireland, the mass of the population had become

increasingly hostile to British rule. In the UK there was a general election

and the Sinn Féin party in Ireland won by a landslide there and started to set

up a republican administration. This was banned by the British and many of the

new Sinn Féin MPs were arrested and jailed.

The Irish

Republican Army (IRA) then began a campaign of armed resistance. Republicans,

however, knew that they could not defeat Britain’s forces in battle – but set

out to make the country un-governable instead. Michael Collins, using

information from a network of agents inside the colonial administration,

directed a ruthless and highly efficient campaign of guerrilla warfare – that

proved difficult for the British forces to defeat.

As the

conflict attracted international attention Britain realised that it was in

danger of losing the propaganda battle, especially after the ‘Great War’ in

which they had claimed to fight for ‘the rights of small nations.’ So, Britain

refused to recognise the conflict as a war and, in an attempt to criminalise

the freedom struggle, the RIC was increasingly used as the front-line force –

with British soldiers, except in areas of high IRA activity, kept in the

background.

In Ireland

non-cooperation, coupled with small acts of sabotage, took place on a daily

basis and the country became an armed camp. Dublin and other cities were

patrolled by troops with fixed bayonets; many of the soldiers had fought in the

‘Great War’ and some said that service in Ireland caused them greater stress

than life in the trenches. But within the RIC there were signs of even greater

strain, both from moral pressure and the armed IRA attacks, which had caused

heavy police casualties with 400 RIC men killed by the end of 1921, compared to

160 soldiers.

In Britain

the politicians’ promises ‘to create a land fit for heroes’ for the returning

fighting men had not materialised. As in the rest of Europe, they were left to

cope on their own, as WW1 front-line veteran George Coppard explained:

‘I joined the queues for jobs as

messengers, window cleaners and scullions … Single men picked up twenty-nine

shillings per week unemployment pay as a special concession, but there was no

jobs for the “heroes” who haunted the billiard halls as I did. The government

never kept their promises.’

Instead,

like in Germany and Italy some of Britain’s WW1 veterans were recruited again,

but this time to fight against the Irish people who were seeking their

independence. Rank and file ex-soldiers joined a unit nicknamed the Black and

Tans, while a number of their former officers joined a more formidable force,

the Auxiliaries. They were both ordered to serve in Ireland with the RIC, to

add an extra-brutal physical-force element to their colonial policing

operations.

The Black

& Tans

The

Auxiliaries and the Black and Tans, once recruited and trained, were shipped to

Ireland and billeted in RIC barracks – to provide a cutting-edge for repressive

operations. Before their arrival the RIC Divisional Commissioner for Munster,

Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth, had called his men to a meeting at the Listowel

police barracks and told them that the British Government had instructed him to

implement a new policy, which he enthusiastically outlined:

‘I am getting 7,000 police from

England.

If a police barracks is burned,

the best house in the locality is to be commandeered.

The police are to lie in ambush

and to shoot suspects. The more you shoot the better I will like you … No

policeman will get into trouble for shooting any man.

Hunger strikers will be allowed

to die in jail – the more the merrier.

We want your assistance in

carrying out this scheme and wiping out Sinn Féin.’

Some

policemen were against the coming of the Black and Tans and this new aggressive

policy. About 500 RIC men tendered their resignations and some walked out after

incidents in their barracks. Daniel Francis Crowley, who served in the RIC from

1914 to 1920, explained what happened at the Listowel barracks after

Commissioner Smyth had given his men their new orders:

‘Sergeant Sullivan spoke

immediately and said that they could tell Colonel Smyth must be an Englishman

by his talk, and that they would not obey such orders; and he took off his coat

and cap and belt and laid them on the table. Colonel Smyth and the Inspector,

O’Shea, ordered him to be arrested for causing dissatisfaction in the force,

but nineteen of them stood up and said if a man touched him, the room would run

red with blood. The soldiers whom Colonel Smyth had with him came in, but the

constables got their loaded rifles off the racks, and Colonel Smyth and the

soldiers went back to Cork. The very next day they [the RIC men] all put on

civilian clothes and left the barracks.’ [The Irish Police by Séamus Breathnact, Anvil Books

1974].

Many of the

RIC men who tried to resign were intimidated, threatened and some were even

whipped by the Black and Tans after they arrived. Crowley, who resigned ‘because of the misgovernment of the English

in Ireland’, fled the country under Black and Tan threats after his friend

Constable Fahey was shot by them. Despite the disaffection within the RIC the

‘new policy’ was quickly put into operation and aggressive actions were

launched against the Irish people, with ‘martial law’ declared in areas thought

to be sympathetic to the IRA and Sinn Féin:

‘Perhaps the biggest single act

of vandalism committed in Ireland by British forces, including the police, took

place on 11-12 December 1920, when Cork city’s centre was sacked and burned …

Cork, of course, was only one of many areas to suffer under the policies which

motivated police and military excesses. Florence O’Donoghue noted that in ‘one

month these “forces of law and order” had burned and partially destroyed

twenty-four towns; in one week they had shot up and sacked Balbriggan,

Ennistymon, Mallow, Miltown-Malbay, Lahinch and Trim …’ [The Irish

Police by Séamus Breathnact, Anvil Books 1974].

The Black

and Tans and the Auxiliaries became a law unto themselves and went on to gain

notorious reputations for waging a campaign of British state-terrorism against

the Irish people. Their activities are still remembered in Ireland and rebel

songs are still sung about them:

The

Connaught Rangers Mutiny

During

Victorian times, as more and more soldiers had been required to conquer and

subdue for the ever expanding Empire, many had came from previously colonised

peoples – including the Welsh, Scottish and Irish. Thomas Macaulay, an

historian and Whig politician, writing about the pay of the British soldier

said that:

‘it does not attract the English

youth in sufficient numbers; and it is found necessary to supply the deficiency

by enlisting largely from among the poorer population of Munster and Connaught.’

Most of the

British Army’s Irish regiments were named after their unit’s catchment areas,

like the Connaught Rangers, the Munster Regiment, the Dublin Fusiliers and the

Leinster Regiment etc. In India in 1920, the 1st Battalion of the Connaught

Rangers were serving at Wellington Barracks at Jullundur in the Punjab. Most

men of this Irish regiment of the British Army were WW1 veterans and some

became disturbed by accounts of the Anglo / Irish conflict – the activities of

the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries, reported by family and friends back home,

became especially resented.

These

feelings came to a head when a number of the troops refused to ‘soldier on’

till the Black and Tans were removed from Ireland. The colonel called a parade

and made an emotional appeal to the mutineers, recounting the many battle

honours won by the regiment, who were nicknamed the ‘Devil’s Own.’ At the end

of his speech Private Joseph Hawes stepped forward and spoke:

‘All the honours on the Colours

of the Connaught Rangers are for England. There is none for Ireland, but there

is going to be one today, and it will be the greatest honour of all.’

It was just

over a year since the Amritsar Massacre and some of the men were sympathetic to

the Indian independence movement. They felt that they were being used to do in

India what other British forces were doing in Ireland. To ensure that their

protest would be noticed, the men took control of their barracks. Some wore

Sinn Féin rosettes on their army uniforms and the Union Jack was lowered and an

Irish tricolour, made from cloth some soldiers had purchased from the local

bazaar, was flown instead. The first time the flag of the Irish Republic had

been raised abroad.

The

Connaught Rangers’ mutiny was put down when the men were surrounded by other

army units, arrested and then court-martialled. During the trial Sergeant Woods

from England, who had joined in with the men, was asked why events in Ireland

should have affected him. Woods, who had won the DCM in France, replied, ‘These boys fought for England with me, and I

was ready to fight for Ireland with them.’

Sixty-one

men were convicted of mutiny and fourteen were sentenced to death – only one

was executed, however, and the sixty other soldiers received long terms of

penal servitude. On 2nd November 1920, 22 year-old Private James Daly, who had

led an unsuccessful assault on the armoury at Solon in which two of his

comrades had been killed, was shot by an army firing squad. He is still

remembered in Ireland:

While in

India, some of the veterans convicted of mutiny were savagely beaten by NCOs of

the Military Provost Staff Corps while in military prison. Then, handcuffed and

in leg-irons, they were sent by train to the coast, to await a ship to England

where they were expected to complete their sentences. As they boarded a

troopship:

‘A curious crowd of both Indians

and Europeans watched their embarkation from the quay side, and to these, the

men of The Rangers addressed ironic shouts of: “Freedom for small nations? See

what you get for fighting for England”!’ [Mutiny for the Cause, by Sam Pollock, Leo Cooper

Ltd 1969].

From Dublin to Jerusalem

The British

authorities had thought that the policy of using the Black and Tans and

Auxiliaries was killing two birds with one stone. On the one hand it rid

British society of a possible source of trouble – disaffected veterans – and on

the other, pitched them into direct conflict with another more pressing problem

– the rebellious Irish. Their aggressive actions in Ireland, however, had

greatly increased IRA support, rather than removing it.

In the end,

as the war in Ireland ended in stalemate and compromise, the Black and Tans and

the Auxiliaries were pulled out in disrepute. In June 1922, the Connaught

Rangers and three other Irish British Army regiments, recruited from areas that

were now part of the new Irish Free State, were disbanded. The mutineers were

released from jail a year later. Joseph Hawes, a Connaught Rangers WW1 veteran,

who was one of those imprisoned for mutiny, later said:

‘When I joined the British Army

in 1914, they told us we were going out to fight for the liberation of small

nations. But when the war was over, and I went home to Ireland, I found that,

so far as one small nation was concerned – my own – these were just words.’

Britain was

forced to withdraw from most of Ireland, but held on to six of the nine

counties of Ulster – by partitioning Ireland and creating Northern Ireland. In

which, after 1969, several new decades of ‘The Troubles’ were to reoccur. The

use of the Auxiliaries and the Black and Tans in Ireland was an early example,

in the modern age, of an imperial powers using special units, outside of the

usual command structure, in an attempt to intimidate a population. Foolishly,

rather than learn the lesson from Ireland – that oppression often breeds

resistance – this practice, of using special units to carry out

state-terrorism, would be used more and more in future conflicts.

After being

used as fodder for the guns in the ‘Great War’ and then sent to Ireland to

fight the Irish, many former veterans and next Black and Tans, or Auxiliaries,

were then re-recruited again and sent to Palestine to reinforce the Colonial

Police there. Operating under Britain’s Palestine Mandate and the Sykes / Picot

Agreement of 1916, from which Britain and France had carved up the territories

of the former Ottoman Empire.

Douglas

Valder Duff was a WW1 navy veteran, who served with the Black and Tans in

Ireland. Afterwards, in 1922 Duff joined up for the Palestine Police Force and,

following his promotion to Inspector, he gained a fearsome reputation for

applying excessive brute force against the local inhabitants, which became

known as ‘duffing-up’ among his fellow members in the Security Forces. Many of

today’s upheavals in this area of the world can be traced back to this period

and the colonial political double-dealing, coupled with the brutal armed

actions of Britain’s colonial police and soldiers at that time.

Forging our Own Chains

Just over

two decades after the end of the ‘War to end all Wars’ the world was at war

again. The great shock and loss felt by many people after WW1, plus the

economic ‘Great Depression’ a decade later, had led to attempts to moderate the

effects of aggressive market-led capitalism. In the US Franklin D. Roosevelt’s

New Deal and the Keynesian Welfare State, implemented by the Labour Government

in the UK after WW2, were examples of this.

This more

caring form of capitalism, with its NHS in Britain, started to create a more

equal society at home, but it was never applied overseas. By the end of WW2 the

USA was established as the world’s leading capitalist power and, after

unleashing a ‘Cold War’ against the communists, they also undertook many

actions to dominate global resources. Across the world numerous democratically

elected governments were ousted by US organised coups d’état, including Iran in

1953, the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1961, Brazil in 1964, Indonesia in

1967, Bolivia in 1971 and Chile in 1973.

Meanwhile, a

subordinate and almost bankrupt UK was squeezing its remnants of Empire for

more profit, while trying to combat, or at least control, the mounting demands

for freedom from colonial rule. Alongside the British Army, colonial Police

Forces played a major suppressive role in places like Malaya, Cyprus, Kenya and

Aden. Although Westminster claimed their forces were ‘peace keepers’ amid

‘bandits,’ ‘extremists’ and ‘terrorists’, in reality it was a callous process –

red in tooth and claw – with free-fire zones, shoot-to-kill squads, brutal

prison camps and massacres.

Throughout

the ‘Emergency’ in Malaya, for instance, the build up of the Security Forces

was on such a large scale that the British Survey of June 1952 stated that:

‘In some areas there is an armed

man to police every two of his fellows, and more than 65 for every known

terrorist …’

At that time

Malaya was producing over a third of the World’s natural rubber and, in 1948,

soldiers of the Scots Guards had rounded-up and killed 24 unarmed villagers on

a rubber plantation near Batang Kali. As news of the massacre leaked out, the

authorities claimed that the victims were ‘bandits’ and ‘terrorists’, who had

been shot trying to escape.

In 1953 the

High Commissioner of Malaya, General Sir Gerald Templer, stated in his yearly

report that a ‘main weapon in the past

four years has been … the sevenfold expansion of the Police …’ And Victor

Purcell, a former colonial civil servant, observed:

‘There was no human activity from

the cradle to the grave that the police did not superintend. The real rulers of

Malaya were not General Templer or his troops but the Special Branch of the

Malayan Police.’

In 1969, two

years after the last British troops were withdrawn from Aden, soldiers were

ordered out onto the streets of Derry in Northern Ireland and another round of

‘The Troubles’ started. The colonial policing role had been passed on from the

RIC to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), with King George V, in 1922,

granting the force the ‘Royal’ prefix. The RUC were armed and operated from

fortified buildings and their personnel were nearly 100% Protestant.

In 1969 the

RUC had numbered around 3, 000, a decade later they had a combined strength of

11,500 with 7,000 regulars and reserves of 4,500. A number of RUC special units

were also set up, with some being trained for shoot-to-kill operations by the

SAS. Others, like the Black and Tans before, became a law onto themselves –

with some colluding covertly with Loyalist paramilitaries.

Back in

Britain, during the Miners Strike in 1984, police from various areas of the

country were organised as a militia against the strikers – in a modified form

of what was already occurring in the North of Ireland. Many of the Security

Services other covert procedures from ‘Ulster’ were also used, like

surveillance, phone tapping and the use of agents, informers and provocateurs.

Combined with the media smearing the strikers and the justice system

criminalising them, all of this helped to ensure the downfall of the Miners.

A century

before, Karl Marx had been a critic of British rule in Ireland and in 1870 he’d

observed that:

‘Ireland is the only excuse of

the English Government for maintaining a big standing army, which in case of

need they send against the English workers, as has happened after the army

became turned into praetorians in Ireland …’

Marx meant

this as a warning and his words were later shortened into: ‘A nation that oppresses another forges its own chains’.

Once again,

over a century later in the 1980s, the conflicts in Northern Ireland and the

Falklands, plus the defeat of the mineworkers, were key elements in enabling

the ‘Iron Lady’ and her Tory Government to establish Neoliberalism in the UK.

The downfall of the Miners was aided by methods and stratagem developed during

military operations in the North of Ireland and the defeat of the strike

weakened the power of the Trade Unions. All of which was used to facilitate the

overthrow of the Keynesian economic system and see it gradually replaced by

market-led and regulation-free pure capitalism.

Thatcher’s

coming also saw individualism lauded, while communities and unions were

denigrated, as this new, more virulent, form of capitalism was established:

Neoliberalism

has seen a return to an exploitative word-wide market-led system, which is

every bit as immoral and vicious as laissez-faire was in the past. Removing the

regulations from financial businesses caused the banking crisis in 2008, which

affected – and with its accompanying austerity still affects – everywhere and

everyone. In both rich and poor countries divide and rule has returned in full throttle,

setting ‘us’ against ‘them’ and vice versa – causing disarray among the many,

to the benefit of the few.

Across the

world raw materials are extracted and used solely for profit, with no thought

given to people, or the environment. The inhabitants of poorer countries find

themselves trapped by corrupt governments with starvation wages and adverse

working conditions. Many die every year trying to migrate to the richer west,

with some trying criminal traffickers – only to find they are enslaved for the

sex-trade, or labour gangs.

To uphold

the retrenchment of a market-led system, new forms of imperialism are used and

the use of the Armed Forces and coercive policing has again become the norm.

And now, around the world, strongman leaders abound, often turning to

neo-fascist traits and a revived nationalism to stay in power. However, those

in whose interests Neoliberalism is imposed are in numbers very much lesser

than those it is inflicted on.

So, perhaps

the biggest question we all need to ask ourselves is: ‘Why do we allow this

type of political and economic system to be dumped on us over and over again?’

Neoliberalism, like laissez-faire in the past, is elitist and un-democratic and

seeks to control our lives. It requires repressive policing just to keep it

afloat and while it remains, although profits multiply in the pockets of the

few, for the rest of us – the vast majority both at home and abroad – we

continue to face conflicts, declining living standards, environmental

destruction, subjugation, misery, starvation and death.

…………………………

Information

compiled and written by VFP member Aly Renwick, who served in the British Army

for 8 years in the 1960s.

Suggested Further Reading:

On the Peterloo Massacre:

On the Victorian Expansion of Empire:

On William Cobbett:

On the Amritsar Massacre:

On the ‘Emergency’ in Malaya and the Batang Kali

Massacre:

On neo-colonisation and military coups:

For a fictionalized

account about how the Neoliberal economic and political system came to

dominance in the UK read ‘Gangrene’, which can be obtained from VFP at:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please submit your comments below