How Disabled People Were Singled Out as part of the Austerity Offensive

SOCIALIST DISABILITY GROUP MEETING

Register here:

https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZYpdemgqD0qHtC2Q-lBqGAVoJCAAKZMLXf3

The Socialist Disability Group

(SDG) is holding an online meeting on Friday 25 March called “SHAFTED — how disabled people found

themselves on the front line.”

Disabled people have been the main

sufferers of the pandemic, of the austerity that came before it and generally

of government policies. Now, new legislation will cut benefits, make it more

difficult to apply for help and cut many off from vital NHS services through

privatisation and enormous waiting lists. This can not go on. As Christine

Tongue of the SDG and the meeting’s organiser said:

We have to take action. We need a bold, grassroots fightback which will make our presence visible. It’s too easy for the world — especially politicians — to ignore people with disabilities. We’re not going to let that happen.

The main speaker at the meeting will be Paula Peters of

Disabled People Against the Cuts, a group known for taking direct action and

mounting imaginative protests.

But a special feature of the event will be contributions from

the floor. Christine said:

We will have members of our network telling their

own stories and saying what they would like politicians to do about their

problems. But able or disabled, we welcome all to this meeting.

Disability and illness is a lottery. Anyone can get it. The point about a

civilised society is that we recognise that we have a duty of care to those who

fall victim to disability.

My first experience of disability was when I was told I had

Hepatitis C in 2012. I went on to experience chronic liver disease and cirrhosis

of the liver. I had had hepatitis for 20+ years. I was however lucky in the

sense that new non-interferon treatments were coming on stream.

Interferon, which was the only method of treating Hep C previously

is an extremely toxic drug. I was first

treated with it in 2013, along with 2 other drugs, and after a couple of months

I discovered that although it was killing the virus it was also killing

me. I spent 18 days in intensive care as

a result.

In the summer of 2014 I was one of an initial 500 people nationally, part of a special government programme, who were judged to be the most sick, who were put on the new Harvoni treatment. You had to take 1 tablet a day for 3 month. Each tablet cost $1000 dollars even though it cost $1 to make. As Gilead Sciences, the company which made the drug freely admitted, they were charging what the market would bear, even though their pricing policy meant that thousands of people died as a result. What was worse was that most of the research for the drug had been carried out at Cardiff University. This is capitalism at its rawest. See Big Pharma Prepares to Profit From the Coronavirus

From 2013 to 2015 when I had a liver transplant I experienced

what it was like to be old and frail. Taking more than a few steps was an

effort. Walking to the shops was an ordeal. Taking part in political protests

was simply impossible and I had to withdraw from the Sodastream protests that

Brighton PSC were engaged in.

My first consciousness of what it was like to be disabled though

was when I was Vice-President Welfare of Brighton Polytechnic Student Union,

some 45 years ago! Disabled students who felt left out by the union suggested

that the best way of understanding what they experienced was for me, as the responsible

official, to navigate a campus in a wheelchair. Falmer was chosen as it was the

most hilly.

It was an eye opening experience to realise the difficulties

in reaching for handles that were too high or doors that were too heavy to open

or steps that made even getting into a building difficult. Toilets were even

more of an obstacle.

Things have improved since that time. Then disability toilets

were the exception. Automatic doors had

not yet made an appearance. Ramps instead of or in addition to stairs were very

much the exception. But if some of the

worst obstacles have been eliminated (& see Christine Tongue’s article for

the Isle of Thanet News below) then the attacks on disabled people’s right to a

decent living have not abated.

People won’t remember that in the 1970s there was no

disability discrimination legislation. That was only introduced under John

Major’s government as a result of our membership of the European Union. And the

first Act was made as weak as possible. It was, for example, possible to

justify both direct and indirect discrimination on grounds of cost whereas

today direct discrimination can never be justified. The same was true when age

discrimination laws were introduced.

Disability benefits have been under attack ever since the

introduction of Disability Living Allowance in 1992, which unified all previous

disability benefits and extended them to those with mental health difficulties.

DLA was a good benefit because it was not means tested and because other

earnings were disregarded. That was why it soon came under attack from New

Labour. A campaign by the Daily Mail and the tabloids was launched against

‘bogus’ disability claimants who we were told were bankrupting the country.

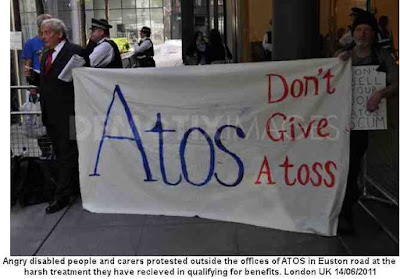

All Work Tests were introduced run by companies such as ATOS

with the clear purpose of getting as many people as possible off benefits.

Incapacity Benefit was abolished by New Labour and towards the end of the

Labour Government a Green Paper was issued by the Health Secretary Andy Burnham

which floated the option of abolition of DLA for the over 60s (after all

getting old means getting infirm!) or at the least abolishing Attendance

Allowance. Burnham himself refused

to deny that these options were on the table.

It was New Labour that set the scene for the Cameron

Government and Ian Duncan Smith’s attack on the living standards of claimants

generally and disabled claimants in particular. Introduced by the 2012 Welfare

Reform Act it was a replacement for DLA for all those above the age of 16. It

was meant to cut the cost of DLA by 20% whereas in fact it has risen.

Now that the COVID pandemic is considered by the government

to have gone away (which it hasn’t) we can expect further government attempts

to cut and restrict disability benefits as they embark on a new period of

austerity.

Below is a lightly edited article by Ellen Clifford in

Tribune in November 2020 and an article by Christine Tongue, of the Socialist Disability

Group and a Steering Committee member of the Socialist Labour Network.

Tony Greenstein

Britain’s

War on Disabled People

In 2016, the

UN said austerity had created a ‘human catastrophe’ for Britain’s disabled —

but the last decade has also seen unprecedented organising to fight back.

Prior to

2010, the UK government was known as a world leader on disability. A decision

was made under the Coalition government and carried forward by successive

Conservative administrations that this progress had gone too far. This marked

the first time in the history of modern social policy that things went

backwards for disabled people. This was done in order to make disabled people

pay for a financial crisis that they did not cause. It needed to be concealed

from the public. The way in which right-wing politicians and the media achieved

this was by creating a narrative that blamed disabled people themselves,

purposefully stoking fires of division and hatred.

What the

government did is one half of the story. The other half is the resistance

mounted by disabled people themselves. If the Tories imagined that disabled

people would be easy targets for their brutal cuts, they were wrong. Again and

again, the government was forced into U-turns and concessions. These discrete

wins along the way have not been able to halt the overall regression in

material conditions for disabled people, wiping away the hard-won gains of

generations of disabled campaigners before us. After more than a decade of

tireless resistance against austerity and welfare reform, the odds against us

have grown even greater.

Targeting Disabled People

In 2016, the

UK became the first country in the world to be found guilty of grave and

systematic violations of disabled people’s rights. This was the finding of an

unprecedented investigation by the UN Disability Committee into the impacts of

welfare reform and austerity measures. What was of concern was the rolling back

of the rights of disabled people, driven forward, the inquiry revealed, by

deliberate legislative and policy choices.

Regressive

measures, badged as government ‘reforms’, were pushed through by the Coalition

government in the face of sustained opposition. As a consequence, disabled

people experienced negative changes within all areas of our lives. In 2018, the

Equality and Human Rights Commission warned that

‘[d]isabled people are falling further behind in many areas, with many

disparities with non-disabled people increasing rather than reducing’, and they

called on the government to urgently adopt an ‘acute focus on improving life in

Britain for disabled people’.

Measures

implemented in the name of austerity and welfare reform have had a

disproportionate impact on disabled people. This was the truth behind David

Cameron’s lie that ‘we are all in it together’. Cuts to benefits (excluding

pensions) and local government made up 50 per cent of the 2010 austerity plan.

Disability and carers benefits make up about 40 per cent of non-pension

benefits and social care makes up 60 per cent of local government expenditure.

Thus, the decision to target spending reductions in these two areas

automatically led to extensive cuts to income and services for disabled people.

The

combination of cuts in benefits and services was found to hit disabled people

on average nine times harder than most other citizens in research carried out by

the Centre for Welfare Reform. For disabled people with the highest support

needs, the burden of cuts was found to be nineteen times that placed on most

other citizens. Contrary to the government’s repeated claim to be ‘protecting’

and ‘targeting resources’ on ‘the most vulnerable in society’, the cuts were

effectively aimed at disabled people.

At the same

time, decisions were made to benefit the rich and help households with the

highest incomes. A 2019 report from the Fabian Society identified how changes

to tax and benefit policies since 2010 have contributed to Britain’s crisis of

inequality, revealing that the government is providing more financial support

for the richest 20 per cent of households than the poorest 20 per cent.

Human Catastrophe

Evidence before us now and in our

inquiry procedure as published in our 2016 report reveals that social cut

policies have led to a human catastrophe in your country, totally neglecting

the vulnerable situation people with disabilities find themselves in.

– Theresia Degener, chair of the United Nations Committee on the Rights

of Persons with Disabilities

These words

were addressed to representatives of the UK government during the concluding

session of a routine public examination of the UK under the United Nations

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. It took place less than

a year after the government dismissed the findings of the committee’s special

investigation.

Death and

suicides linked to cuts and benefit changes are the most extreme example of the

human cost of austerity and welfare reform, but there have been many other

terrible impacts, including rising poverty, food-bank use, debt, survival

crime, and homelessness, in addition to dramatically escalating levels of

mental distress. A study by academics from Liverpool and Oxford Universities

published in 2015 found that reassessments for Incapacity Benefit from 2010 to

2013 were associated with an extra 590 suicides, 279,000 additional cases of

self-reported mental health problems and the prescribing of a further 752,000

anti-depressants. Victims of welfare reform who have died or taken their lives

as a direct consequence of benefit cuts are now a common item on daily media

coverage.

Legislation

and policies that have inflicted such suffering have also largely failed to

deliver their stated aims. The transition from Disability Living Allowance

(DLA) to Personal Independence Payment (PIP) was intended to save 20 per cent

compared with DLA remaining in place, but it appears to have cost around 15 to

20 per cent more. A report from the Office for Budget Responsibility

published in January 2019 estimated an overspend on the DLA/PIP budget of £2

billion, leaving an estimated £4.2 billion shortfall when compared to the

original savings target.

On a societal

level, cuts to local authority budgets threaten disabled people’s continued

existence in the community alongside non-disabled people. Funding cuts to

education and social care and a failure to invest in accessible social housing

are leading us towards physical re-segregation and institutionalisation.

Alongside this, there has been a fuelling of attitudes that ‘other’ and thereby

marginalise disabled people: on the one hand, growing disadvantage, resulting

from cuts to state-funded support and leading to greater reliance on charity,

has encouraged a pitying view of disability; on the other, hatred and hostility

towards disabled people have been enflamed by anti-benefit-claimant rhetoric

used by the government to justify welfare reform.

Political

Fallout

A government

does not attack its own citizens en masse without consequence. The

impacts of austerity and welfare reform on disabled people have played a

significant but overlooked role in the political upheaval of the last ten

years. In terms of retaining control of Westminster, the Tories were largely

correct in their assumption that — as Iain Duncan Smith observed — ‘[disabled people] don’t vote for us’,

and thus that their attacks on disabled people would not affect their chances

of re-election. Nevertheless, Cameron’s miscalculation on the EU referendum can

be attributed to his failure to adequately understand the impacts of his

policies and the bitter anger towards anything regarded as ‘establishment’.

Welfare

reform has politicised large swathes of people. Experiences where individuals

have their benefits stopped are obviously traumatic for those affected, but all

benefit claimants are now subject to a benefit assessment approach which is

personally humiliating. Trauma, confusion, and anger can turn to demoralisation

and distress, but they can also lead to politicisation and activism. Research

by the University of Essex and Inclusion London found that, in order to make

sense of their situation, claimants came to think about their difficulties

within the context of politics and Tory attacks on disabled people. Those who

adopted an attitude of resistance towards the system and/or became politically

engaged were better able to restore a sense of self-esteem that had been taken

from them by their interactions with the Department for Work and Pensions

(DWP).

Issues

affecting disabled people have the potential to cause far greater social

upheaval than the public and political profile of disability suggests. Disabled

people make up 22 per cent of the population, a figure that is often

underestimated. We are geographically and generationally dispersed across the

population. Issues relevant to us also affect our friends, family, neighbours,

and the range of workers whose jobs are linked to disability. Lack of recognition

for the social significance of disability issues within politics and the media

reinforces in those experiencing them the idea that their lives are not valued

by those in power, making them hungry for a change from the status quo.

Forefront of the Fightback

With the

Disabled People’s Movement (DPM) in decline from the mid-1990s, resistance from

2010 onwards can be characterised as a return to grassroots activism. In a

conscious departure from the identity politics era of disability campaigning,

new groups such as Disabled People Against Cuts (DPAC) were set up with the

explicit aim of building alliances and joining the wider anti-capitalist

movement.

One of the

ways in which the British government was able to get away with making war on

disabled people was by the sheer volume and complexity of the measures they

unleashed. Where disabled people and their allies succeeded in holding them

back was through intense and varied activity operating on many fronts and

involving many people, each making an invaluable contribution in their own way.

Resistance has used every tool at its disposal — from research, lobbying,

protests, endless legal challenges, awareness-raising, and direct action.

Collectively, the stakes are too high to give up and give in.

Since 2010,

campaigners have won significant victories such as forcing Atos, a global

corporation with a revenue measured in billions, out of its contract to deliver

the Work Capability Assessment. The government has been free to ignore

the UN disability committee findings but it was a considerable achievement for

grassroots disabled activists to secure the unprecedented special investigation

that took place from 2015–16. The findings served to validate the experiences

of millions of disabled people under attack from their own government. The

government’s failure to slash the DLA/PIP budget can be attributed to the hard

work of campaigners, claimants, advisers, and public lawyers who have

consistently resisted attempts by the DWP to introduce measures limiting eligibility

for the benefit.

Disabled

activists have been at the forefront of the anti-austerity movement. Despite

our efforts, the direction of government policy is further regression of

disabled people’s living standards. One of the impacts of this is that it is

becoming harder for disabled people to mobilise resistance.

The War Goes On

In December

2019, the most right-wing government in modern British history was re-elected

with a significantly increased majority.

This was

disastrous news for disabled people. Under Boris Johnson, the Conservatives now

had the parliamentary power not simply to carry on in the same direction with

the continuation of policies that have spread inequality, poverty, and

immiseration, but to ramp up their attacks and implement welfare reform

measures that they were previously beaten back from achieving.

An early

indication of what the election result meant for disabled people was the

decision announced in the New Year’s honours list to award Iain Duncan Smith a

knighthood. Duncan Smith had not held a ministerial appointment since his

period as secretary of state for work and pensions from 2010 to 2016. The

honour effectively endorsed the dismantling of the social security safety net

over which he presided. It also suggested full government commitment to rolling

out Duncan Smith’s big idea, Universal Credit, in spite of the well-evidenced

harms it has caused.

Into this

picture, we then had the Covid-19 outbreak. The pandemic exposed existing

inequalities within society even more starkly than a decade of austerity and

welfare reform had. Disabled people were at the same time most at risk from

coronavirus and also largely ignored in official responses to the pandemic. At

a time of great uncertainty and anxiety, disabled activists and health workers

had to challenge NHS guidelines that stated that disabled people were not a

priority for life-saving treatment. Two thirds of deaths from coronavirus in

the UK are disabled people. Between 15 March and 2 May, 22,500 disabled people

died from Covid-19 compared to 15,500 non-disabled people.

Campaigners

suspect that Boris Johnson’s original strategy of seeking to create ‘herd

immunity’ and the government’s failure to do more to protect disabled people

was part of a deliberate plan to remove from society those whose lives are

deemed to represent a cost burden on the state. This is not inconceivable. Both

Johnson and his close adviser Dominic Cummings have expressed views described

by researcher-activist Roddy Slorach as ‘textbook

examples of eugenic opinion’.

Speaking to

city bankers during his time as mayor of London, Johnson said:

Whatever you

think of the value of IQ tests it is surely relevant to a conversation about

equality that as many as 16 per cent of our species have an IQ below 85 while

about 2 per cent have an IQ above 130 … the harder you shake the pack the

easier it will be for some cornflakes to get to the top. And for one reason or

another — boardroom greed or, as I am assured, the natural and God-given talent

of boardroom inhabitants — the income gap between the top cornflakes and the

bottom cornflakes is getting wider than ever.

Inequality

is a state that Johnson and Cummings both regard as natural and even desirable

for the functioning of society. It is nevertheless important to remember that

the war against disabled people cannot just be attributed to individual

ministers or Tory governments. Its existence is bound up with the intrinsic

relationship between disability and capitalism.

What has

happened since 2010 is a sharp reflection of the fundamentally important role

that the category of disability plays within capitalist political economy,

where it serves to identify the less productive members of society and enables

a ‘weeding out’ from the rest of the population. Interrogating the relationship

between disability and capitalism is a powerful way to expose the inequalities

and cruelty of the system of exploitation under which we live. It is no wonder

then that disability issues are so hidden and misunderstood within mainstream

society: they need to be shrouded in myths and misconceptions in order to

obscure the true nature of capitalism.

Those of us

who want a fairer world must fight for improvements in the living conditions of

disabled people as part of — not in isolation from — the rest of the working

class. But our resistance must also be consciously situated within the struggle

to transcend capitalism itself. Only then can we guarantee freedom from

oppression and a society where diversity is truly valued.

Opinion

with Christine Tongue: Mentioning the unmentionables

Look away now if you feel squeamish about talk of lavs, pants

and pads and toilet issues in general.

My friend Mandy who has an undiagnosed neurological

problem, said to me “I sometimes can’t do two things at the same

time. Standing up from the loo and pulling up my pants was just too much today.

I fell flat on my face — hence the new bruises!”

My friend Sue, wheelchair user, has to use incontinence pads

at night when getting to the loo involves hoists and transfers to a special

bathroom wheel chair. But the pads she could get free from NHS supplies are not

comfortable or adequate. She has to buy her own. A large weekly expense.

Some disabled people have catheters into their bladder —you

pee into a bag beside your bed. It’s convenient but leaves you prone to

infection.

I’m not at that stage yet, but with my failing legs and

painful back, going to the loo is now a much more difficult process. Social

services have provided metal surrounds and raised toilet seats for my home. But

going outside your house is a minefield.

I’ve just had to get my long suffering partner to carry one

of my toilet frames to a friends house. Last time I used his loo I nearly fell

over trying to hold onto his bath and a door handle —the door opened, I lurched

into the cupboard etc etc. You get the picture….

Why aren’t all houses designed with potential disability in

mind. Whose mad idea was it to put in low toilets in modern bathrooms with no

grab rails around them? Most people are taller than me so have a long way to

haul themselves up from a low seat.

But public loos are not ideal. They may have wheelchair on

the door but it doesn’t mean all disabled people can use the space.

The disabled loo in Broadstairs harbour needs a “radar” key

to get in —just in case you able hooligans go in and use it for antisocial

behaviour I guess. It’s a kind of master key for most disabled public loos. Nothing

electronic about it and anyone can buy one. But for me, even though I now have

a radar key I bought on the internet, I would have to stand outside, reach for

my key, put my sticks in one hand, or prop them up on the wall in order to use

the key. Mandy might have fallen over by now.

You get inside and need to lock the door. Another balancing

act. But oh joy, two bars on each side of the loo to grab and lift yourself up

with. I wonder how others get on with washing their hands. For me it’s another

balance problem with no stick to lean on and sometimes a distance to the hand

dryer.

The other disabled loo at Broadstairs bandstand doesn’t need

a key and is easy to get into on my scooter — which gives you a safe stable

object to hang onto. Which you need because there’s a lack of grab rails and

the hand dryer is the other side of the room from the sink. Take a clean hanky

and give it a miss is my advice.

People using the dryer will inevitably drop water

on the floor. A wet floor and sticks is not good! Which is why I like to take

the scooter in with me. I can’t risk slipping. My bones are rebellious enough

without shaking them up sliding on a wet floor.

What I’m talking about is often down to basic design. You

won’t fall over if you have a grab rail in the right place. If you need pads

and special pants let’s make sure the people who need them get the best

available. As for public lavs, let’s make them accessible, clean, safe. Not

locked! Why not?

Erudite and thought provoking articles. Thank you so much Christine and Tony and for the ground breaking meeting with Paula Peters. Disability must never be forgotten.

ReplyDelete