German Volunteers in the French Resistance and the story of Anti-Fascist Germans Fighting an ‘Anti-Patriotic’ War

Book Review:

Anti-Nazi Germans: Enemies of the Nazi State from within the Working Class Movement (Merilyn Moos) & German Volunteers in the French Resistance (Steve Cushion),

Community Languages (with the Socialist History Society), 2020, pp. 316, £10, ISBN 978-1-9163423-0-9

As the blurb on the back of the book says,

it is a commonly held belief that there was very

little resistance in Germany to the Nazis, except for one or two well known

instances. But, regularly ignored or forgotten is the level of opposition from

anti-Germans and in particular from the German working class movement.

When

I told a friend that I was reviewing a book on the German Resistance, she

responded by saying that it must be a remarkably thin book then! I responded by

saying that no, it was over 300 pages at which point she quipped that it must

be in a very large print size! No I

responded, if I have any criticism of the book it is that the print is too

small and the footnotes are almost unreadably tiny.

The

German working class has been written out of the history of Nazism. It is a

common belief that only the Jews were murdered and but for Churchill and Roosevelt

we would be goostepping our way to work today. The contribution of the Soviet

Union of course is either minimized or ignored.

This

book is therefore a welcome contribution to rectifying the historical record

and I recommend it to anyone who seriously wants to understand what the level

of repression was that the opponents of Hitler had to work under. As the

Introduction says,

‘this book does not aim for objectivity. It is unashamedly

written to honour the resistance which had its roots in the working class

movement.’ [1]

Zionist

historiography treats all Germans as one undifferentiated mass. They were all

Jew haters, regardless of class. The best known of these is Daniel Goldhagen’s Germans: Hitler’s Willing Executioners

in which he posits that:

the vast majority—not all, but the vast majority—of

ordinary Germans during the Nazi

period were prepared to kill Jews.

Goldhagen

argued that Germany during the Nazi period had a political system that was both

dictatorial and consensual. Despite the widespread belief that Jews were the primary

victims of the Nazis, the first victims of the Nazis were communists and trade

unionists. It was they who were imprisoned in Dachau, the first concentration

camp which was established in March 1933.

As

Ian Birchall notes in the Preface, in the first years of the Nazi regime it was

the working class who were their main target not the Jews. Only 5% of the first

camp inmates were Jewish. Even by 1937 there were only hundreds of Jewish men

in the camps, imprisoned because they were communists not because they were

Jews. Indeed in the 1932 Presidential election between Hitler and Hindenburg

Hitler’s programme didn’t even mention the Jews.

Moos

estimates that at least 3,000 Jewish Germans were involved in the illegal

German workers and youth movements in the first phase of the resistance. ‘They were generally not from a Zionist

background where the emphasis was on emigration to Palestine.’ (189) The

Zionist youth organisations were legal until 1939 (the non-Zionist ones having

been banned in 1936).

Some

3 million Germans became political prisoners during the Nazi era and as many as

200,000 were detained in 1933 alone, including 60,000 communists, of whom 2,000

were murdered.

By

the end of the war about 150,000 KPD members had been detained, of whom at

least 30,000 were executed. Some 1 million leftists were imprisoned in camps of

whom 200,000 were murdered.

To

those who dismiss the German resistance and that of the millions of slave

labourers we should remember that only half the planned number of V2 flying

bombs were produced for use against Britain in 1944-45 because of go slows and

sabotage. As Merilyn Moose remarks ‘some

Londoners will have owed their lives to these acts of bravery.’

The

main resistance to the Nazis was the German Communist Party, the KPD. The

Social Democratic Party (SPD), put up virtually no resistance and indeed was a

party to the repression. In 1918/19 it had set the Freikorps on the workers in

the German revolution and in 1929 in Berlin the Prussian SPD government ordered

the Police to fire on the May Day demonstrators. On 22 January 1933 the KPD

leadership appealed to the SPD leaders to co-operate in opposing the Nazi march

on the KPD headquarters, Karl Liebnicht House in Berlin. What the KPD should

have done was to appeal to the SPD base but calling them social fascists wasn’t

the best way of winning them over.

The

SPD leaders said that they would only use legal means to oppose the Nazis. In

other words they surrendered, in the name of bourgeois legality, to the Nazis. As

our own Labour Party shows, the leaders of the SPD were political cowards and

reactionary. However the base of the SPD’s support was the German working class

and it was these people whom the KPD’s ‘social fascist’ slogans alienated.

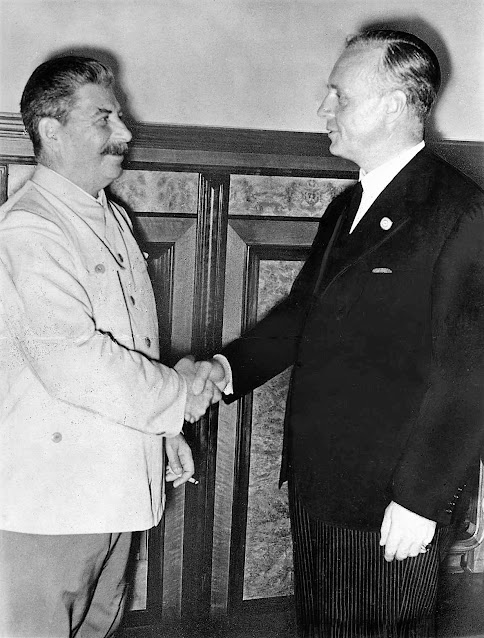

Stalin-Ribbentrop

The

decision of Stalin and the KPD leaders to adopt the ‘Third Period’ position

that the social democrats were social fascists was criminal. What it was saying

was that workers who supported the SPD were no better than the lumpen rabble

that made up the Nazi party’s base. As late as February 1932 the KPD CC were saying

that the SPD and the Nazis were ‘political

twins and equally evil.’ (47)

It

was not until the summer of 1935 at the 7th Congress of the

Comintern that the Third Period line was abandoned for Popular Frontism. But the KPD leaders clung to the old position

until 1936.

Steve

Cushion compares the Nazi seizure of power in Germany to the successful

mobilisation of workers in France who prevented an attempted fascist coup in Paris

as being the final nail in the coffin of the Communist International’s Third

Period.

Moos

points out that Trotsky was urging the KPD to form a united front with the SPD

and workers who supported it. He raised

the slogan ‘March separately but strike

together’. Unfortunately Trotskyists

were in a political minority.

The

reason for the Third Period line was Stalin’s belief that Hitler coming to

power would cause problems for the British and French. The German working class was sacrificed on

the altar of Russian foreign policy. The signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop

Pact in August 1939 was the logical continuation of this policy. Stalin used the

Pact to repatriate to Germany hundreds of communists who had fled Germany for

the Soviet Union. (56)

The

Pact was a disaster both for the Communist Party and the anti-fascist movement.

The needs of the Stalinist rulers of Russia spelt disaster for Communist

Parties in other countries. In France it gave the Daladier government an ideal

excuse to repress the left and introduce the death penalty for membership of

the Communist Party.

When

Hitler took power on 30 January 1933 the KPD leadership refused to even call a

demonstration. In sign of just how absurd and delusional were the politics of

Stalin’s Third Period, the communist press came out with slogans such as ‘the worse the better’ and ‘After Hitler, it will be us.’

It

didn’t take long for the KPD leadership to learn that the rise of Hitler was not

a victory for German workers. Not until 28 February did the KPD Central

Committee issue a call to the 3 trade union federations and the SPD for strikes

but by then it was too late. (29)

In

1933 53,000 people fled from Germany and 4,000 made their way to the USSR. 70%

of them were to lose their lives in Stalin’s purges.

There

are heroes too numerous to mention in this book such as Wolfgang Abendroth who,

having been expelled from the KPD in 1928 joined the SAP (Socialist Workers

Party). Arrested and imprisoned he was forced to serve in Criminal Division 999.

He deserted to the Greek partisans ELAS and was imprisoned by the British

before becoming a Politics Professor at Marburg University.

Abendroth

was the exception. One of the most depressing aspects of this book are the

numerous members of the resistance who were tortured and executed. That Stalin

facilitated the rise to power of Hitler should serve as a reminder to anyone foolish

enough to believe that Stalin was anything other than a monster and a criminal.

Merilyn

Moos makes the books purpose clear when she says that history has a political

function. It is not a neutral collection of facts. The West German state was

supposed to be de-Nazified but this came to a halt with the Cold War. The

highest civil servant and aide to Chancellor Konrad Adeneur was Hans Globke,

who had been personally

responsible for drafting the Reich Citizenship Law which removed

citizenship from German Jews as well as the ordinance to force all Jews to take

the names Israel or Sarah. He also drafted the laws on Rassenchande which forbade sexual relations between a Jew and

non-Jew. Yet the Israeli state at Ben Gurion’s insistence excluded all mention

of him at the Eichmann Trial. Silence about Globke was part of the price of

German-Israeli rapprochement after

the war.

As

late as 1956 the Bundestag voted to compensate the widows of SS

officers whilst denying compensation to the widows of murdered communists,

whose party was outlawed.

The

book details the confrontations between Communist militants and the Nazi SA on

the streets of Weimar Germany. These confrontations were led by the KPD’s Red

Front but the leadership of the KPD was lukewarm about their activities. The KPD

leadership had embarked on a policy of trying to win over the SA and Nazi rank

and file. That was why not one of the 77 KPD

representatives in the 1930-32 Reichstag was Jewish. The Thalman leadership

acquiesced in the Nazis’ anti-Semitism by excluding Jews.

Another

example of this approach was the joint KPD/SA picket during the transport

strike of 1932. It was as if Stalinism had reserved the united front tactic for

the Nazis. Yet what took place on the streets of Berlin between 1930 and 1933

was ‘something akin to a civil war’.

It

is a myth that with the abolition of the trade unions on May 2nd

1933 that strikes ended. There were more than 200 work stoppages from February

1936 to July 1937 which is remarkable given the presence of the Gestapo in most

major factories. In 1938/39 there was a successful go-slow by the Ruhr miners

against Goering’s wage cuts and even during the war, in one Chemnitz factory

there was a go slow resulting in a reduction of 21% in production.

In

the IG Farben factory in 1939 4 workers were sent to prison for smoking and

‘slackers’ were warned that their names would be handed to the Gestapo. A

number of workers were executed for ‘incitement to strike’ or ‘sabotage’. This

was the benign dictatorship that Zionist historians believe was the lot of

ordinary Germans.

The

SPD put up no resistance in Germany after 1933. Its leaders abandoned ship. The

KPD, despite its ultra-left policies, continued to operate. In 1934 over 1

million papers were distributed in factories and it put out over a million

leaflets until 1935/6. By 1935 of the 422

former KPD leaders, 219 had been arrested, 14 assassinated, 125 had gone

into exile and 10 had left the party.

There

were a number of anti-Nazi splinter groups such as the SAP, which consisted mainly

of those who had left the SPD in 1931. There was the KPD Opposition (KPO) which

broke from the KPD in 1928, over their opposition to the Third Period and its

absurd belief that the workers would spontaneously rise up once Hitler took power.

Willi Brandt

By

the spring 1933 some 15,000 members of the SAP

were involved in resistance work. One of their most prominent leaders, Max

Kohler survived and joined the SPD after the war. Another prominent member was Willi Brandt, the future

Chancellor of Germany.

Alexander Schwab

One

of the most interesting groups was the Rote Kämpfer (Red Fighters). Formed in 1931/2 it consisted of about 400 young

left-wing socialists. They specialised in hiding Jews and had cells in Berlin,

Stuttgart, Hamburg, Karlsruhe and Frankfurt. However by 1936 they had been

infiltrated by the Gestapo and their leader, Alexander Schwab and most of the

members were arrested and executed.

The two main Trotskyist groups were the Left Opposition and the German

section of the 4th International, the International Communists of Germany. The

former had about 600 members and the latter about 1,000. It was especially hard

hit by the rise of the Nazis. Half their members simply deserted and 150 ended

up in the concentration camps. They played virtually no role in the resistance.

Extremely important was the role of youth groups. After the passage of

the Hitler Youth Act of 1 December 1936 membership became almost compulsory.

The rebellion of youth was a combination of culture and politics with a desire to

be free. Jazz music and swing were outlawed by the Nazis as ‘degenerate’. The Edelweiss Pirates

were primarily based in Cologne (Navajos)

though they had a presence in a number of other cities. They were branded

as lazy and the Gestapo declared them a criminal group. One of their favourite

activities was assaulting Hitler Youth patrols.

They purchased arms and staged burglaries and theft. They worse

unconventional clothes, sang anti-militaristic songs and robbed the homes of

the Hitler Youth! On one occasion in 1942 they shot dead a leader of the Hitler

Youth and injured another.

As the war progressed they became increasingly political and in 1943

their graffiti read ‘Down with Hitler,

Down with Nazi brutality. We want freedom.’ (84)

13 Edelweiss Pirates were hanged in November 1944 in Cologne on Himmler's orders

Merilyn Moos writes that in Duisberg around 1943, the Pirates travelled in groups of 60 or 70 and attacked

leaders of the Hitler Youth with brass knuckles. There was a significant

leakage from the Hitler Youth to the Pirates, partly because of a dislike of

the doctrine of ‘Aryanism’.

The Pirates

offered shelter to army deserters, escaped prisoners from the concentration

camps and forced labour camps. They also made raids on arms depots and engaged

in sabotaging war production. From 1941-43 they defied the Nazi regime by

distributing leaflets to working class sections of Hamburg.

This chimes with what I heard when I visited friends in Hamburg. I was

told that at night there were parts of Hamburg, which had been a radical left

city, where the Nazis wouldn’t go unless they were armed.

However the Gestapo hated them. In December 1942 in Dusseldorf the

Gestapo rounded up over 1,000 and they were treated brutally. In Cologne there

was a shoot out between the Pirates and the Gestapo in which the Chief of the

Gestapo was killed. On 25 October 1944, Heinrich

Himmler ordered a crackdown on the group and in November of that year, a group

of thirteen people, the heads of the Ehrenfelder Gruppe, were publicly

hanged in Cologne. The Edelweißpiraten hanged included six teenagers,

among them Bartholomäus Schink, (Barthel), a former member of the local

Navajos. Fritz Theilen survived.

Moos suggest that the Edelweiss Pirates in Cologne contained a network of 3,000 mostly working class kids. The Wuppertal Edelweiss Pirates were predominantly working class and Moos describes them as street kids for whom the Pirates were their family.

Jean Julich

Because the Nazi judges continued on into West Germany, it was not until

2005 that their Gestapo records were expunged. Jean

Jülich: One of the Edelweiss Pirates, who resisted the Nazis

In the mountainous areas of Saxon Switzerland many opponents of the Nazis

organised themselves as outdoor, mountaineering or hiking groups such as the

United Climbing Division (VKA). Their advantage was that they could hold

meetings in lonely out of the way places.

Heinz Kapelle

German

Resistance Groups

The Kapelle

Group continued the resistance in 1938/9 when most groups had been

destroyed and infiltrated. With the invasion of Poland the group produced

anti-war leaflets which they deposited in phone booths and plastered on walls.

However the Gestapo between 15 and 17 October 1939 began a crackdown on

resistance activities and Heinz Kapelle and Erich Ziegler were arrested and

tortured. Kapelle was murdered at Plotzensee prison in Berlin in July 1941.

Robert Uhrig

The Uhrig group spanned both periods of resistance, before and after war

broke out. Led by Robert

Uhrig, a member of the KPD, by the beginning of 1942 Uhrig had links with

89 factory groups and cells in several factories in Berlin, especially Siemens.

Amongst the many heroes of the group was Werner Seelenbinder,

a wrestler and KPD member who refused to give the Hitler salute when receiving

his medal at the German Wrestling Championship. He was given a 16 month ban on competing

but was allowed to participate in the 1936 Olympic Games. He became active in

the Uhrig group as a courier in 1941 but in February 1942 he was arrested with

65 others. Severely tortured on 24 October 1944 he was beheaded.

The Gestapo had infiltrated the group and Uhrig and 200 others were

arrested also in February 1942. Uhrig was sent to Sachsenhausen KZ and

guillotined on 21 August 1944.

Bernhard Bastelein

Another group was the Bastelein group which mainly organised in Hamburg.

By December 1941 the group had cells in about 30 Hamburg factories, shipyards

and wharves. In October 1942 the Gestapo uncovered their activities and of

their 200 activists 100 were arrested and 60 sentenced to death. Bernhard

Bastelein was moved in August 1943 to Potzensee prison in Berlin where he would

almost certainly have been executed but for the fact that in January 1944 the

prison was bombed and he escaped.

The Saefkow-Jacob

Bastlein Organisation had a membership of about 500 and in 1943-44 it was

probably the biggest and most active of resistance groups. About 30 of the

group were involved in relief operations for Jews. The group concentrated on

making contacts with foreign slave labourers in factories such as Askania.

As the war progressed and more Germans were called up, so millions of

slave labourers were imported into Germany to keep the wheels of production

moving. Even Jews, who had been deported

to make Germany Judenrein, were brought back to work in the factories.

|

| Gad Beck |

One group who I wish to single out is the Baum group.

It was the only organised and sustained Jewish resistance group in Germany. It

included both Zionists and Communists. One such was Gad Beck,

a gay Jewish Zionist. 3 months before the Nazi surrender he was betrayed by a

Jew working for the Gestapo. However he survived.

Herbert Baum

Merilyn Moos writes that the leader, Herbert Baum saw himself primarily

as a communist not a Jew. Many young Jews regarded communism as the answer to

the political crisis in Germany and were antagonistic to a collective Jewish

identity, seeing it as bourgeois.

Today with the advent of the State of Israel and its replication of the racial

supremacist politics of Nazi Germany we can but pay tribute to those Jews who,

whilst fighting the Nazis opposed Zionism.

There was also a relatively high proportion of women involved in the Baum

group, almost all of whom were involved in the firebombing

of the Soviet Paradise exhibition in Berlin’s Lustgarten on 18 May 1942.

Marianne Baum

The Soviet-Paradise exhibition was staged by Goebbels as an attempt to

show the poverty and degradation of the Soviet Union. It was believed that the

destruction of the exhibition would awake the spirit of resistance in the

German working class.

Unfortunately the planning and implementation was inept but they managed

to burn down a small part of the exhibition before fire fighters arrived. Most

of the group were arrested soon after and they were sentenced to death and

executed in Berlin-Plotzensee prison.

Although consisting of mainly communists the Baum Group condemned the Hitler-Stalin

pact from the start. Towards the end of the Nazi regime the size of the anti-Nazi

opposition was considerable in some places. In Hamburg an Anti-Fascist

Committee was established with 700 communists and others, 200 of whom were

organised as military units. In the Blohm und Voss shipyard 250-300 workers

were organised into anti-Nazi groups.

Resistance

Towards the End of the War

In Bremen the communists had about 200 activists. Lubeck KPD had about 30

members with a group of 225 armed Germans and foreign workers. In Hanover the

Gestapo discovered frequent acts of sabotage and in Leipzig armed uprisings

were planned. As the Allies approached they issued a leaflet calling for no

resistance and in fact they succeeded in ensuring that there was no firefight.

In Cologne the opposition was particularly strong but the Allied bombing

was particularly heavy and created hostility to the Allies.

Moos mentions the National Committee for a Free Germany (NKVD) which was

created by the Soviet Union in July 1943 in a POW camp. The Soviets pursued a

strategy of trying to turn German POWs against Hitler. The NKVD’s name was

revealing. ‘Germany needs to be freed

from Hitler, not transformed into a socialist society.’

There were also links between the NKVD and the aristocratic Kreisau

Circle whose figurehead was Helmuth von Moltke

on whose estate the group met. Moltke was arrested on 19 January 1944 in

connection with the purges of resistance elements within the Abwehr. He was executed in January 1945

though his wife Freya carried on the struggle. The circle aimed for a social

democratic and humanist Germany after the war as part of a united Europe.

Unlike much of occupied Europe, in Germany in the last years of the war working

class resistance movements were all but smashed. ‘There remains the question as to how far the Comintern contributed to

Nazism’s demise.’

By late summer 1944 some 7.6 million foreign workers and POWs were

working in Germany. They comprised between 25% and 40% of all workers. The

Nazis did not want to employ ‘animals’ in their strategic industries but they

had no choice. ‘Economic need trumped

ideology and foreign forced labour became the backbone of the German war

economy.’ Not just Russians but up

to 200,000 Hungarian Jews were employed. However sexual contact with German

women was punished by public execution.

Up till May 1940 more than 1 million Polish workers were employed in

Germany. Indeed in the farms they had vacated the Zionists organised their

kibbutzim, something the Bund condemned as scabbing. There were some 2 million

French workers and 1 million Italians in Germany. The largest contingent, 3

million, was from the Soviet Union, of whom over half were women.

There was a very high rate of arrests for refusal to work. In Berlin in

December 1941 out of 605 arrests 345 were for refusal to work. As Nazi Germany

looked as if it would be defeated from early 1944 onwards so foreign workers

gained in confidence. At the Cologne Klockner

plant sabotage was carried out in the engine plant.

George Schumann

Some Soviet POWs attempted to

build anti-Nazi resistance groups. Very few POWs or other forced labourers

succeeded in making contact with resistance groups but in Munich the resistance

group under metalworker Karl Zimmer did and they formed the Anti-Nazi German

People’s Front. Another group with contacts with Soviet POWs was the Leipsig

group led by Georg

Schumann, a former KPD member of the Reichstag.

The European Union, formed in Berlin in 1939 by Georg Groscurth and Robert Havemann was

about 50 strong. It had high level contacts in the Nazi regime and it wrote a

number of leaflets calling for a united socialist Europe. Saved from the death

penalty because of the value of his work Havemann was dismissed from his

academic post at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin in 1948 because of

American pressure. In 1963 he was dismissed as professor from the Humboldt

University of Berlin in East Germany. He was a permanent dissident.

There is also a section on the communist resistance in the camps,

including Auschwitz and Buchenwald where it saved a number of people including

children. Indeed at Buchenwald the resistance took charge and ousted the SS as

the Americans approached.

At Auschwitz the resistance, which was weaker, gave the warning to the

Sonderkommando that they were about to be murdered which led to the 7 October

1944 revolt and the destruction of one of the crematoria. Unfortunately the

revolt had come too late as the Nazis were already preparing to destroy the

extermination apparatus.

In Flossenburg 100-300 pairs of airplane wings were destroyed though the

reprisals were savage.

There was also considerable resistance within the armed forces,

especially as the situation turned militarily against Germany. One division in

particular, Strafdivision 999 (Criminal

Division 999), which included a high proportion of politicals, simply deserted.

400-500 joined the Greek Resistance. In the end the 999 divisions were disarmed

for fear of further rebellions, especially on the eastern front.

The 999s played a significant part in the Greek resistance and the graves

of those executed were decorated with wreaths and flowers by the Greeks. It is

estimated that of the 12 million German conscripts by the war’s end between

300,000 and 500,000 deserted.

Moos

argues that the ‘disproportionate numbers

and leading role of historically Jewish people in the resistance was largely

ignored until the 1970s.’ Why?

Because the resistance was dominated by communists and historians were

influenced by the cold war.

Jewish

historians were not in general concerned with resistance of a left wing and

illegal form… Both German Jewish historiography and the British based Leo Baeck

Institute had previously largely ignored political resistance to the Nazi

regime by anti-fascists who were only loosely connected to the established

Jewish community. (193)

Also,

with the exception of the White Rose group, underground groups did not

emphasise the anti-Semitic character of Nazism.

There

is a section on Jewish Youth. The Zionist youth groups like Hashomer Hatzair

were legal until 1939. The main non-Zionist group was Kameraden which

split into Zionist, non-Zionist and Communist factions. On occasion the

Zionists took part in resistance activities such as when the socialist Zionist

Borochov-Jugend put out the polemical underground paper Anti-Sturmer a riposte to Julius Streicher’s virulently anti-Semitic

paper.

The

most militant of the anti-Zionist youth groups in Kamaraden was the Schwarzer

Haufen (Black Block) many of whom joined the KPD or the Trotskyists or KPO. Many of its

activists were later captured and murdered.

Because

the left parties and their organisations were banned, many young people who

would have joined left groups joined Jewish groups instead. This helped provide

cover for the recruitment of young Jews for anti-fascist propaganda work and

cemented ties with the KPD. For example many Jewish women were instrumental in

helping to build several communist resistance circles in Berlin.

There

is a chapter on Cologne which out of a population of ¾ million had about 10,000

in the resistance of whom 3,000 were active in the working class movement.

Unfortunately Allies under Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris committed terrible war crimes

when they repeatedly bombed Cologne. Apparently the civilian population dropped

to 453,000 in 1945.

The

resistance was led by the KPD. For every

SPD member arrested there were 20 from the KPD. Because of Cologne’s proximity

to the border it became the link town for the SPD and its exile organisation (SOPADE).

What distinguished Cologne from other places was the role of the Catholic resistance.

A few Catholics, mostly priests and lay officials of the Catholic workers

movement put up active resistance.

A

key feature of Cologne was the importance of foreign labour. By September 1944

there were about 30,000 inmates of concentration camps in Cologne, 40% of whom

were Russian or Ukrainians. From

November on the rate of executions on portable gallows of foreign labourers

increased exponentially.

In

August 1943 alone the Gestapo arrested over 2,000 people in Cologne. From 1944

the Gestapo deported thousands of Cologne Jews apparently and killed over 1,500

Sinti and Roma people, homosexuals and other ‘anti-social’ elements.

By

October/November 1944 the Nazi authorities were close to collapse in Cologne. ‘A diaspora of the disaffected developed.

What happened in Cologne was close to open rebellion, even civil war.’

At

the start of the war the Gestapo targeted the political enemies of the state. Amongst

the first were the veterans of the Spanish civil war. They were deported to

Mauthausen where almost 75% were murdered. Annihilated through labour.

It

is estimated that in the early months of 1945 some 300,000 inmates of the camps

were murdered. Himmler had stated in April 1945 that no prisoner should fall

into enemy hands.

Merilyn Moos

argues that

‘it was the

decimation of the left, the anti-Nazi resistance and its ideological opposition

to Nazism which was an essential prerequisite for the construction of the Jew

as a racialised outsider and the anti-Semitic practices which followed.’

The

precondition for the holocaust was the elimination of the left. Zionist

historians like Yehuda Bauer and Lucy Dawidowicz argued that Hitler was engaged

primarily in a ‘war against the Jews’.

In

the last weeks of the war about 120 anti-fascist groups sprang up. In Leipsig the group had 150,000 supporters.

They urged soldiers to desert and demanded that the Allies should not cause

further destruction. Moos speculates

that the German resistance also helped hasten the end of the war.

German

Volunteers in the French Resistance

The

second section of the book is on German Volunteers in the French Resistance by

Steve Cushion. Steve points out that the large number of foreign fighters in

the French liberation whilst so many French citizens collaborated was

uncomfortable.

Once the German army invaded a campaign of urban terrorism was launched against them culminating in Nice when Max Brings, a Jewish German communist blew up the officers mess after Christmas 1943. Max Brings impersonated an SS officer and entered an SS training centre in Aix en Provence. Together with August Mahnke and other members of the resistance, they obtained the files of the SD (intelligence police) on the resistance and made off with them.

The

Travail allemande was an initiative

in which German speakers infiltrated the occupation authorities in order to aid

the French resistance. French Trotskyists also attempted to spread propaganda

amongst the German soldiers. Both initiatives paid a very high price in terms

of lives lost but there were some successes and some German soldiers were

persuaded to desert or act as informants. But the most important desertions

came from the SS recruits from Eastern Europe and Bosnia who often shot their

German officers.

Veterans

of the Spanish civil war played a key part in organising armed resistance to

the Nazis. With the defeat of the Spanish Republican government thousands of

International Brigaders and a quarter of a million refugees crossed the border

into France. The Communist CGTU trade union federation sought to organise these

and other immigrants into the MOI (Immigrant Labour Force).

Cushion

describes how the large Italian presence in France, over a million and a half

people, were augmented by refugees from Mussolini. They were largely based in the mining regions

and were to the fore in organising a successful week long strike in May 1941.

Despite

skepticism amongst the KPD leadership in France about the Travail Allemande

after 1941 young German speaking women would make the acquaintance of German

soldiers who would be passed on to their superiors. There was a heavy price to

pay and over 100 activists, mainly women were tortured and executed.

However

by August 1944 there were 37 soldiers’ committees, 51 groups comprising between

2 and 5 members and 75 soldiers who joined individually.

An

example of the activity of the communist resistance was that of Wally Heckling,

a courier for the KPD in Paris. She gained employment as an accountant for a

German firm and managed to secure the employment of her comrades. Taking over

the administration of the company they obtained access to stamps that validated

workers’ identity passes as well as employing French comrades on the run.

Berthold

Blank, a member of the SPD in Leipzig, was the first Wehrmacht deserter in Toulouse. He was posted, as a punishment for

returning late, to the Birkenau death camp where he became aware of the

extermination programme. He passed this information on to the writers of Soldat am Mittelmeer.

Walter

Kramer, was an NCO stationed in Toulouse where he ran a Wehrmacht bookshop. He was able to forewarn of a big round-up of

Jews in Toulouse.

Anton Schmid

Sergeant Anton Schmid took

an active part in the Jewish resistance. His apartment in Vilnius was a refuge

for Jewish partisans. In February 1942 he was arrested, tried by a German

military court and executed on 13 April 1942.

In

Italy the Garibaldi Brigades were organised by the Italian Communist Party. The

Piemonte region was a stronghold of

the partisan movement with thousands of combatants by mid-April 1945 whose

activity spilled out into a general strike and insurrection. The partisan

liberation of Italian cities began in Bologna on 21 April 1945.

Martin Monath

Martin

Monath was a Berliner who had been a member of the German section of

Hashomer Hatzair, the socialist Zionist group. HH’s Hebrew language magazine

was permitted in Nazi Germany until 1938 even though it contained some of

Trotsky’s articles! Trotsky of course rejected the idea that the struggle

against fascism should be subordinated to the ‘democratic’ bourgeoisie.

Monath

was involved in contacts between a German soldiers’ committee and the

resistance in Brest. Unfortunately the Gestapo got wind of the group and

during October 1943 25 German soldiers and 25 Trotskyists were

arrested. 12 soldiers were immediately executed.

Martin Monath

Monath

escaped and in early 1944 returned to Paris. Resuming work on the papers Arbeiter and Soldat he was arrested by the French police and handed over to the

Gestapo. He was tortured and shot just days before the general strike and

insurrection broke out in Paris. Another

figure involved in this work was Robert Cruau in Brest who was also killed by

the Gestapo in October 1943.

There

is a fascinating chapter on ‘The

Revolt of the Ost Legion’. The 13th Handzar division consisting

of Bosnian Muslims was formed following the massacre of 2,000 Muslims by Serb

nationalists. The Nazis were approached to form a local gendarmerie for the

protection of local Muslims.

However

it was sent to Villefranche de Rouergue in Southern France in August 1943. All

the officers were Nazis who treated the men with racist contempt. On 16-17

September they staged a rebellion executing their officers. Unfortunately one

of them was only wounded and got away. SS reinforcements captured 100 of the

escapees and shot them but those that got away joined either the French or

Yugoslav partisans.

According

to Stephen Schwartz the Handschar Division had been sent to France for

retraining on the Jewish Question. Cushion details a whole series of revolts by

captured Russians, Ukranians, Azeris and Poles who had agreed to fight for

Hitler. Sent to France to replace German troops who had been sent to the East

they soon rebelled: ‘the

counterproductive nature of German racism now became evident.’

It

was Nazi repression that led to the defeat of a strike by 100,000 miners in the

Forbidden Zone in Northern France. This convinced the miners that they had to

resort to armed resistance. The mine owners worked closely with the Gestapo

handing over names of ringleaders, 270 of whom were deported to the

concentration camps.

One

factory owner remarked that ‘I would rather see my country occupied by

the Germans than my factory by the workers.’ As Cushion observed when the

employers are seen as traitors, the class struggle appears patriotic. However

the Popular Front policy of the Communist Party relegated class struggle to an

alliance with Ango-American imperialism.

‘The main

political outcome of the strike was to provide the French resistance with its

most solid base.’

In

1942 and 1943 over half the armed attacks and sabotage in France occurred in

the Nord-Pas-de-Calais. The tactic of individual assassinations became replaced

by derailing troop trains.

By

1943 with their losses in Russia the Nazis were forced to recruit what was

essentially slave labour from France. 600,000 French workers were sent to

Germany with another 200,000 managing to evade capture. It was massively

unpopular and was an important factor in alienating French public opinion from

the Petain government. It led to the growth of a rural resistance.

Of

the half million Spanish Republican refugees who fled to France some 120,000

were still living in France in 1940.

Both the Nazis and Petain, who was a friend of Franco, had a special

hatred for them. About 15,000 were

interned in French concentration camps.

With

the end of the war these refugees became an embarrassment as Franco was

rehabilitated by the United States as an anti-communist ally. The former heroes

of the resistance became ‘foreign terrorists’.

Gerhard Leo

Gerhard Leo was the son of a Viennese

social democrat, Wilhem Leon. The family moved to France in 1933 after his father

had been released from Oranienburg

concentration camp. He joined the resistance where he edited a German

soldiers magazine Soldat am Mittelmeer.

Betrayed he ended up in Toulouse prison before ending up in front of a German Court

Martial accused of treason.

Oradour-sur-Glane

Because

he had been stripped of his German citizenship he couldn’t be tried for treason

and he was sent to Paris for interrogation and retrial. The train was

intercepted by the Maquis. Leo survived an attempt by the police to murder him

and joined in the successful attack on the regional capital Tulle on 8 June

1944. Unfortunately the SS Das Reich division was en route to

Normandy and Tulle lay in its path. Gerhard was one of 99 people hanged from lampposts. On 10 June the SS Das Reich division destroyed the French town of Oradour-sur-Glane

murdering 642 of its inhabitants – men, women and children.

Cushion

remarks that

‘if the German

volunteers who fought in France are a problem for French historiography then

they are doubly difficult for a nationalist reading of German history.’

PCF,

the French Communist Party, accepted the role of junior partner in the post-war

Gaullist government. Part of the price was buying into the nationalist

narrative and downplaying the role of the FTP-MOI, the immigrant and foreigner’s

section of the French resistance.

As

Cushion says, the decision to form the FTP-MOI had been an ‘unusually far-sighted act of internationalism

that contributed significantly to the fight against fascism.’ Cushion

quotes Robert Gildea as describing the Jewish component as ‘the most militant and effective’ of the

foreign fighters as they were ‘Dead men

on Leave’.

Cushion

concluded that

‘the principal contribution of these anti-fascist activists

is to undermine the idea of a citizen’s loyalty to the Nation as their primary

duty.’

Cushion

and Moos conclude by saying that

‘the present political conjuncture in the UK

includes some frightening similarities with final period of the Weimar Republic’.

I

agree and it is something that those fools on the left who became part of the

Brexit campaign should ponder, in particular those who believed in Lexit, which

was a left version of British nationalism.

Tony

Greenstein

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please submit your comments below