For nearly 20 years Israeli Arabs lived under military rule – not

because they were a Fifth Column but to prevent them returning to the land that

had stolen been from them

|

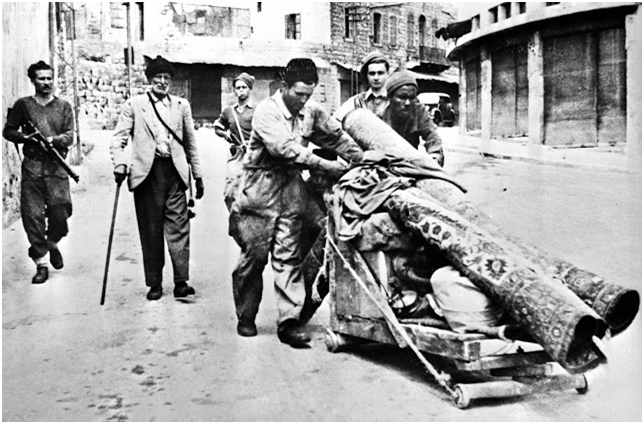

Haganah terrorists expelling Palestinian refugees from Haifa

Israel

is a state that has been built on myths – whether it is that ‘god’ gave the

settlers the land of the Palestinians or the fiction that in 1948, the

Palestinians miraculously ran away on the orders of the Arab states in order

that a Jewish state could be created. As Ilan Pappe, Benny Morris and other historians have demonstrated,

the Palestinians left because they were forced to do so.

I

have previously covered the topic of the desperate

efforts of the Israeli state to prevent the truth emerging. This has taken the

form of reclassifying documents that have been released to historians,

presumably on the assumption that they were not copied and therefore any one

quoting from them can’t prove that what they said is true.

At

the end of this article in Ha’aretz, Adam Raz quotes the cynical

comments of Yehiel Horev, the former director of the Malmab, the secretive

Defence Ministry unit which is dedicated to rewriting the history of the

Israeli military’s deeds. In an interview he made his purposes crystal clear:

“When

the state imposes confidentiality, the published work is weakened… If someone

writes that the horse is black, if the horse isn’t outside the barn, you can’t

prove that it’s really black.”

Of

course all nations based their identity on myths such as the tales of King

Arthur and his knights. Israel’s national myths are not just about ancient

tales of kings but about recent events where the evidence is crystal clear. Myths that are national lies with the sole

purpose of legitimising the theft of land.

| |

|

From

1949 to 1966 Israel’s Arab population was kept under military government. They

could not leave their villages without permission. As is the case with

everything in Israel the excuse was that the Arabs were a fifth column, a

security threat.

We

now know, as the article by Adam Raz explains, that this was never true and was

not believed by the military establishment either. The purpose of military rule

was in order to prevent Israel’s Arabs, who had often been displaced by the

fighting from their villages, from returning to their land.

A

law, the Absentee Property

Law was passed in 1950 with the specific purpose of defining the

property of persons who were expelled, fled or left the country after 29

November 1947 as well as their property (land, houses, bank accounts etc.), as

“absentees”.

Property

belonging to absentees was placed under the control of the Custodian for

Absentees’ Property. The Absentees’ Property Law 1950 was the main legal

instrument used by Israel to take possession of the land belonging to the

internal and external Palestinian refugees.

| |

|

An

Orwellian category Present-Absentees was created. You could be present in

Israel, having not been expelled, and still be absent. Even if you left your house in 1948 because

of the fighting or you were forced out by the Haganah you are still counted as

an Internally Displaced Person. Of course Israeli Jews who were forced to leave

their homes face no such prohibition.

It

is estimated today that 1 in 4 Israeli Palestinians are Internally Displaced

Persons. That lies at the root of inequality in Israel, an inequality

emphasised by the Jewish Nation State Law that made ‘Jewish settlement’ into a

national virtue.

IDPs

are not permitted

to live in the homes they formerly lived in, even if they were in the same

area, the property still exists, and they can show that they own it. [Tom Segev,

1949: The First Israelis, pp. 68-91].

However it was one thing to pass a racist law but

it was another thing to implement that law. Israeli Palestinians desired

nothing more than to return to where they were living but for Zionism, all

wings of the Zionist movement including the ‘left’ Mapam, it was an article of

faith that no Palestinian should ever return to their home even if they only

moved a mile away for safety.

Thus it was that military rule was instituted over

Israel’s Palestinian population. By

forbidding them to leave their villages without permission it made it that much

easier to prevent unauthorised access to their previous homes. This was

necessary because although Zionist settlers moved into their former villages

this took time, not least because at that time there weren’t enough Zionist

settlers.

Thus Israel was born in a fit of ethnic cleansing

and today the job of Malmad and the Ministry of Defence is to keep documents of

the time secret and hidden and to perpetuate the myth that the Palestinian

refugees left of their own accord.

Tony

Greenstein

A document unsealed after 60 years

reveals the Israeli government’s secret intentions behind the imposition of a

military government on the country’s Arab citizens in 1948: not to enhance

security but to ensure Jewish control of the land

Jan

31, 2020 11:50 AM

|

Arabs awaiting a security check in Kfar Qasem, during the War of Independence.GPO

Israel’s

defense establishment has for years endeavored to conceal historical

documentation in various archives around the country, as was revealed in an

article in Haaretz last July.

That

article, which followed up on a study by the Akevot Institute for Israeli-Palestinian

Conflict Research, noted that for closed to 20 years, the staff at Malmab – the

Defense Ministry’s secretive security department (the name is a Hebrew acronym

for “director of security of the defense establishment”) – had been visiting public and private archives and forcing

their directors to mothball documents relating to Israeli history,

with special emphasis on the Arab-Israeli conflict. This was done without legal

authority. The article sparked a furor, and dozens of researchers and

historians urged the defense minister at the time, Benjamin Netanyahu, to halt

the clandestine illegal activity. Their appeal received no response.

When the state imposes confidentiality,

the published work is weakened… If someone writes that the horse is black, if

the horse isn’t outside the barn, you can’t prove that it’s really black.

What

sort of documents did Malmab order the directors to hide away in their archives’

safes? The many and varied examples include: thick files kept by the military

government under which Israel’s Arab citizens lived for 18 years; testimony

about the looting and destruction of Arab villages during the Independence War;

cabinet ministers’ comments on the Arab refugee situation, following that war;

evidence of acts of expulsion and testimony about camps set up for captives;

information about Israel’s nuclear project; documents relating to various

foreign policy issues; and even a letter sent by the poet and Holocaust

survivor Abba Kovner about his own anti-Arab sentiments.

It’s

not clear whether Malmab has reduced its activity in the archives since the

article was published. However, it can be said that during the past six months,

files earlier ordered closed by Malmab have been reopened, adding to our

knowledge of the history of the two peoples who share this land. Though none

are earth-shattering in historical significance, these are important documents

that shed light on significant aspects of various events.

One

such document is a secret codicil to a report drawn up by the

government-appointed Ratner Committee in early 1956. The document, restored

from oblivion in a safe at the Yad Yaari Research and Documentation Center at

Givat Haviva, is titled, “Security Settlement and the Land Question.”

The

importance of the information included in the codicil can be seen within the

context of the history of the military government imposed on Israel’s Arabs in

1948, just months after independence, and abolished only in 1966. There were

about 156,000 Arabs in Israel at the war’s end. Following the armistice

agreement with Jordan (April 1949) and the annexation of the Triangle – a

concentration of Arab locales in central Israel – 27 villages, from Kafr Qasem

in the south to Umm al-Fahm in the north, also fell under the jurisdiction of

the military government.

Administratively,

the latter was divided into three regions: north, center (Triangle) and Negev.

Sixty percent of Israel’s Arab citizens lived in Galilee, 20 percent in the

Triangle and the rest in the Negev and in various so-called mixed cities, such

as Haifa and Acre. In practice, about 85 percent of all Arab citizens were

under the rule of the military government, subject to night-time curfews and

regulations requiring them to obtain a travel permit before leaving their area

of residence.

Related

Articles

- Burying the Nakba: How Israel

systematically hides evidence of 1948 expulsion of Arabs

- Land swap in south,

population swap in north: Israel and Palestine according to Trump

The

military government was based on the Defense (Emergency) Regulations,

promulgated in 1945 by British mandatory authorities, and invoked by Israel to

facilitate supervision of the movement and settlement of its Arab citizens, and

to prevent their return to the areas captured by Jewish forces in the

Independence War. The Jewish public was told that the purpose of the military

government was to deter hostile actions against the state by its Arab citizens.

In practice, however, it only exacerbated the enmity between the two peoples.

|

|

|

The secret addendum. Described the military government as a tool in the struggle against Arab "trespassers.

|

The

military government, an ugly episode in Israeli history, was the subject of

severe criticism at the time, not least by certain members of the Jewish

community. Various parties on both the left and the right – Ahdut Ha’avodah,

Mapam, the Communist Party and Herut (precursor of Likud) – objected, each for

its own reasons, to its imposition. One reason for the opposition was that, as

early as the early 1950s, the Shin Bet security service had concluded that the

country’s Arab citizens did not pose any sort of security risk.

Opinion

was also divided in Mapai, the ruling party (precursor of Labor). The state

committee that was headed by Prof. Yohanan Ratner, a retired general and

architect, was the second body appointed to consider whether the military government

was necessary. The first, convened by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, in 1949,

had decided to leave the status quo in place. In February 1956, the three

members of the Ratner Committee reached the unanimous conclusion that

“the

military government has been reduced as much as it can be, and there is no

place for a further reduction.”

That

this was probably a foregone conclusion is attested to by a remark made in

public by a member of that panel, Daniel Auster (mayor of Jerusalem until

1950):

“Of

200,000 Arabs and other minorities now residing in Israel, we did not find one

who is loyal to the state.”

Secret

action

A

few years later, in the early 1960s, when pressure mounted to abolish the

military government, Ben-Gurion explained that it was still essential in order

to prevent an insurrection by the country’s Arabs. The state’s existence

depends on the presence of the military government, he maintained, although he

did not mention the opposition to it of the security establishment. However, it

gradually became clear that what truly interested the advocates of the

government was not security but control over land. That had been facilitated by

Article 125 of the Defense (Emergency) Regulations (1945), under which a

military commander can issue an order to close “any area or place.”

In

a closed meeting of the Mapai leadership, in 1962, Ben-Gurion stated that

without article 125, “we would not have

been able to do what we did” in the Negev and Galilee. “Northern Galilee is Judenrein [empty of

Jews],” he warned.

“We

will find ourselves in that situation for many years if we do not prevent – by

means of Article 125, by administrative force and military force – entry into

forbidden areas. And in the eyes of the Arabs these forbidden areas are theirs.

Because the land of Ayalon [Valley] is Arab land.”

Despite

the inherent logic of this argument, few testimonies exist about the military

government’s latent nationalist motivations. For one thing, there was a tacit

understanding, rarely violated, that this was not a subject for public

discussion. The secret appendix to the Ratner Committee’s report, found in the

Yaari Archives and in the State Archives, and being published here for the

first time, is highly illuminating about the true motives that guided the

country’s leaders.

According

to the panel, the army alone could not safeguard state lands: only Jewish

settlement – “security settlement,” as it was called – could do that in the

long run. It was thus essential to establish Jewish settlements in the three

geographical zones overseen by the military government. Such a process,

however, would be lengthy, the committee members agreed, and in the meantime

Arab citizens uprooted in the war wanted to return to their homes – something

that could not be prevented through legislation. In the view of the codicil’s

framers,

“The laxness [by the Arabs] in seizing these

areas is due mainly to the fact these areas were closed by the military

government or under its supervision.”

They

added that only

“the

vigilance of the military government’s representatives largely prevented more

serious lawlessness in regard to land seizure.”

In

other words, it was that government that prevented the Arabs from returning to

their lands.

The

report’s authors also objected to a decision made by Pinhas Lavon, a senior

Mapai figure who opposed the military government and who replaced Ben-Gurion as

defence minister in early 1954 (but resigned a year later during the so-called

Lavon affair, which involved a covert operation in Egypt that went wrong). Lavon

cancelled the prior decision to divide Galilee into 46 separate, closed areas

in which Arabs needed a permit to move from one to another. A division into

three or four zones would be enough, to his mind, and would ease life for Arab

citizens. The committee members were adamantly against this, arguing that it

had led to excessively free movement by the Arabs, because of which “the takeover of the state’s lands increased.”

The

Ratner Committee exceeded the official mandate it received upon its appointment

in late 1955. Its secret codicil also includes detailed recommendations for

amending property laws, particularly an Ottoman statute from 1858. The latter

stipulated that anyone, Jew or Arab, who resided on land for 10 years

consecutively, was entitled to retain it permanently. Now, eight years after

Israel’s founding, the committee was worried that within two years, much land

would be lost and transferred to Arab citizens. Its recommendation, then, was

to abolish the time frame in regard to remaining on these lands.

The

text of the secret codicil shows unequivocally that a major task of the

military government was to act as a means to control the state’s lands until

their permanent status could be regularised and until, with state support,

Jewish settlement could begin in formerly Arab areas. Hence, one of the

committee’s conclusions:

“Until

the stabilisation of security settlement in the few reserve areas that can

still be settled, it is essential to maintain the military government in these

places and to strengthen its apparatus… so that the military government can

ensure, directly and indirectly, that the lands are not lost to the state.”

The

panel described the military government as a tool in the struggle against Arab

“trespassers,” and added that without the military government, “many more areas are liable to be lost to

the state.” In a reprimand to the state, the committee noted that the

military government was suffering from “known

laxness… as a result of the criticism being levelled at it.”

Published

in part at the time (without the secret section), the Ratner Committee’s

recommendations provoked considerable public and governmental criticism.

Ben-Gurion, who received a copy of the report in February 1956, blocked

discussion of it for months because of disagreements within the government. The

Sinai War, which erupted in October 1956, meant that it stayed off the agenda

for an even longer period. Ultimately, the report was never submitted to the

government for approval, but nevertheless served as the basis for policy in the

coming years. In 1958, another committee, headed by Justice Minister Pinhas

Rosen, suggested far-reaching changes in the military government, effectively

proposing its almost total abolition. Not surprisingly, the cabinet held

lengthy discussions in 1959 about whether to publish the recommendations of the

Rosen committee.

Why

did the state continue to conceal a report that was written more than six

decades ago? The explanation might lie in a cabinet session in July 1959, in

which Education Minister Zalman Aranne stated that “among the conclusions are some that are political.” In other

words, security had nothing to do with it. He added,

“The thing must be done, but not revealed,

such as Judaizing Galilee, for example.”

Perhaps

it’s appropriate here to recall the words of Yehiel Horev, the former director

of the Malmab, who admitted in an interview to Haaretz last July that the

defense establishment is simply trying to hamper historians.

“When

the state imposes confidentiality, the published work is weakened… If someone

writes that the horse is black, if the horse isn’t outside the barn, you can’t

prove that it’s really black.”

Adam

Raz, a historian, is a researcher at the Akevot Institute for

Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Research and author of the book “Kafr Qasem

Massacre: A Political Biography,” published in both Hebrew and Arabic.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please submit your comments below